This post was initially published as part of Affording Your First Home.

In its reception however, though knowing what you're getting into is integral to getting a loan responsibly, the mechanics of a loan isn't something that's going to be on a test that has to be passed in order to qualify for a home loan, so it was more of a distraction than an integral part of that post.

So now it lives on its own post for anyone who wants to take a peek into how residential mortgages work, saving 5,000+ words off of an already-dense read.

Why Bother?

Why bother understanding how home loans work, indeed? Don't you just keep earning more and spending less, and it should be good from here on?

Well, yes, if you're alright with buying one property and stopping there.

With a blank canvas, it doesn't matter if your loan is inefficient in terms of its financial impact to the rest of your life, but what if you want to buy another property, take time off to care for your aging parents, or get different kinds of loans to start a business?

What if you have to go back to study for a specialisation, in order to get paid more?

What if you're 60, and only now that you discover that you don't qualify for a 30-years home loan anymore, so you have to sell the family home just to continue living?

What if you don't want a life that's optimised to paying down a home loan, but rather, a full life where a mortgage is but an inconsequential part of it?

A contract is such that even if you don't understand the rules, you still have to abide by the rules.

But if you understand the rules, you plan ahead and set up your own terms, so that you can design a life that’s on your terms, and learn how to fit those loan contracts into it.

The Ideal Borrower

The ideal borrower is a 30-50 something, with 30 years of fulltime employment ahead of them.

If you fit within this category, congratulations. The odds are in your favour.

Why fulltime employment?

There are 2 fundamental assumptions in finance:

- Volatility is risk.

- Stability is safe.

Translated, it becomes:

- Unpredictability is risk.

- Predictability is safe.

The person who earns $0—$200,000 p.a. is riskier than the person who earns a stable $80,000 p.a.

A business owner who has 1000 things to pay (and potentially be liable) for, with fluctuating income, is riskier than a limited responsibilities, regularly paid, various-work-insurances-hedged employee.

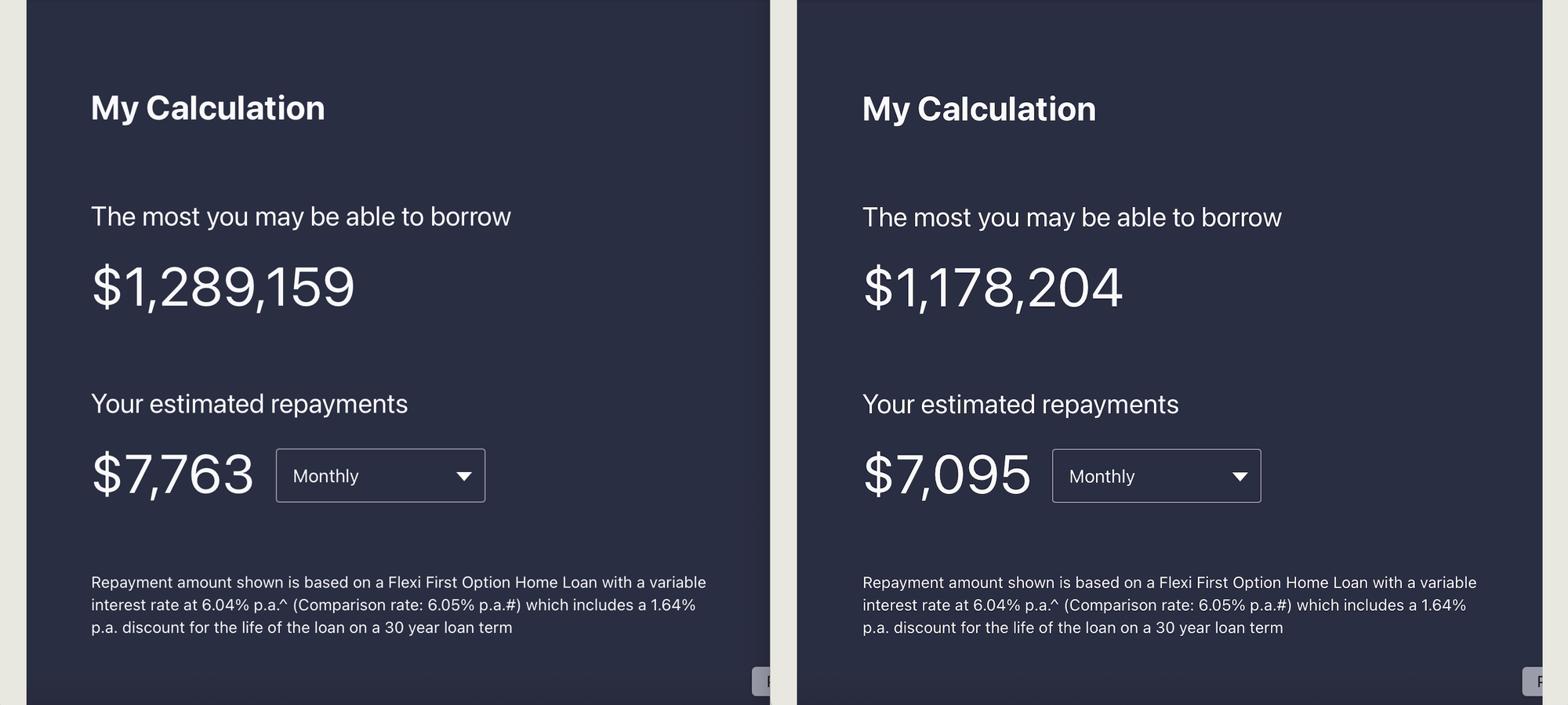

In particular, fulltime regular incomes are more valued than variable incomes, such as bonuses or overtime payments. They still add to the amount you can borrow, but regular incomes have more weight in the underwriting, so a $250,000 base salary is more valuable than a $150,000 base + $100,000 bonus, even though they total to the same amount. You can test this on any banks’ borrowing calculators.

Why 30 years?

The short history of it was that what the US sneezes, Australia catches. With the wartime 30-year bonds having a successful market uptake, the enterprising country thought, "what else is not a bond, but is bond-like?" The answer to that was housing.

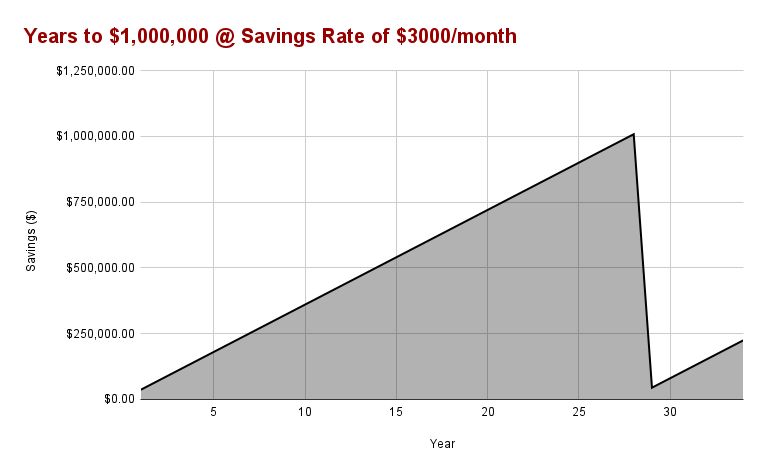

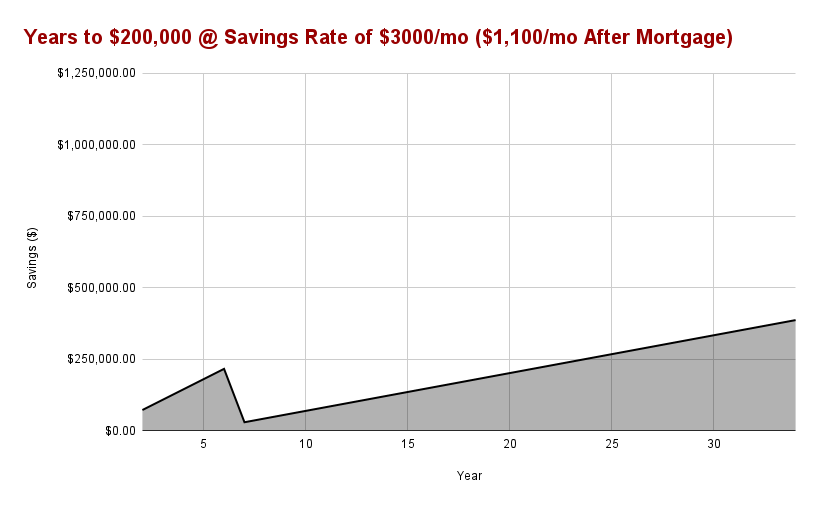

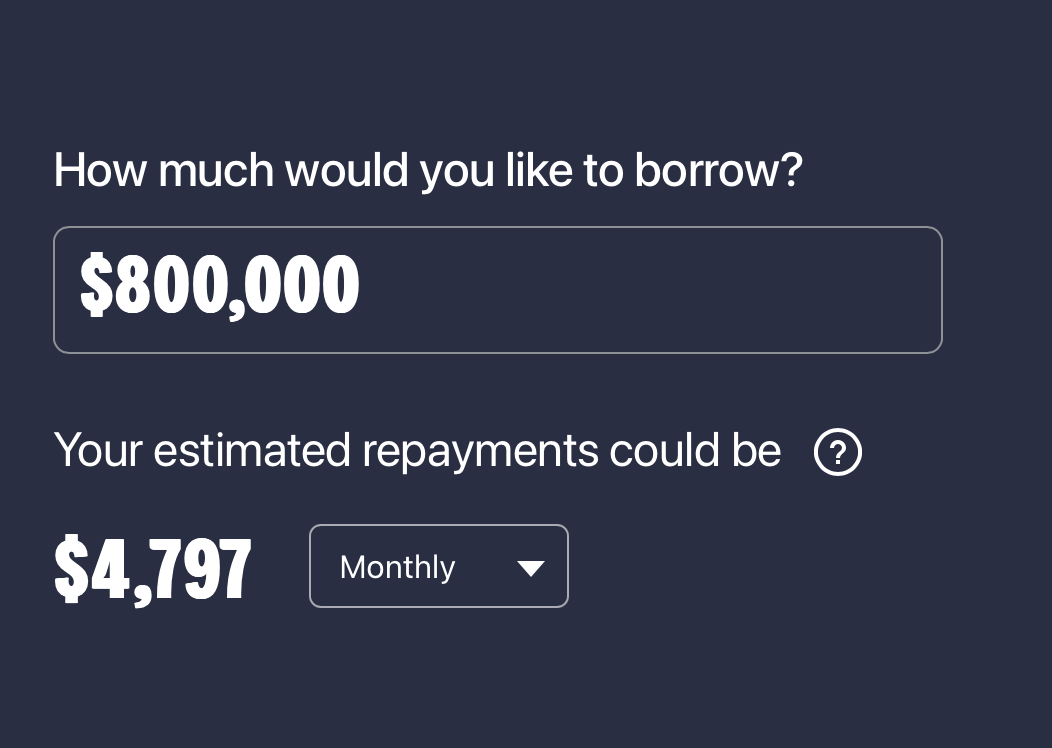

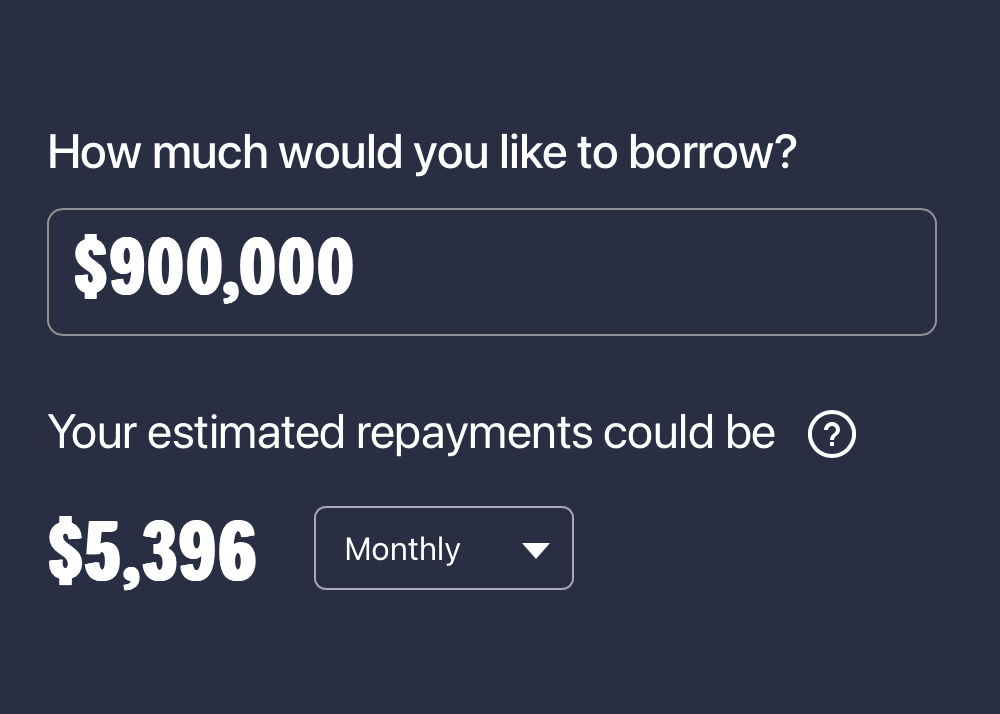

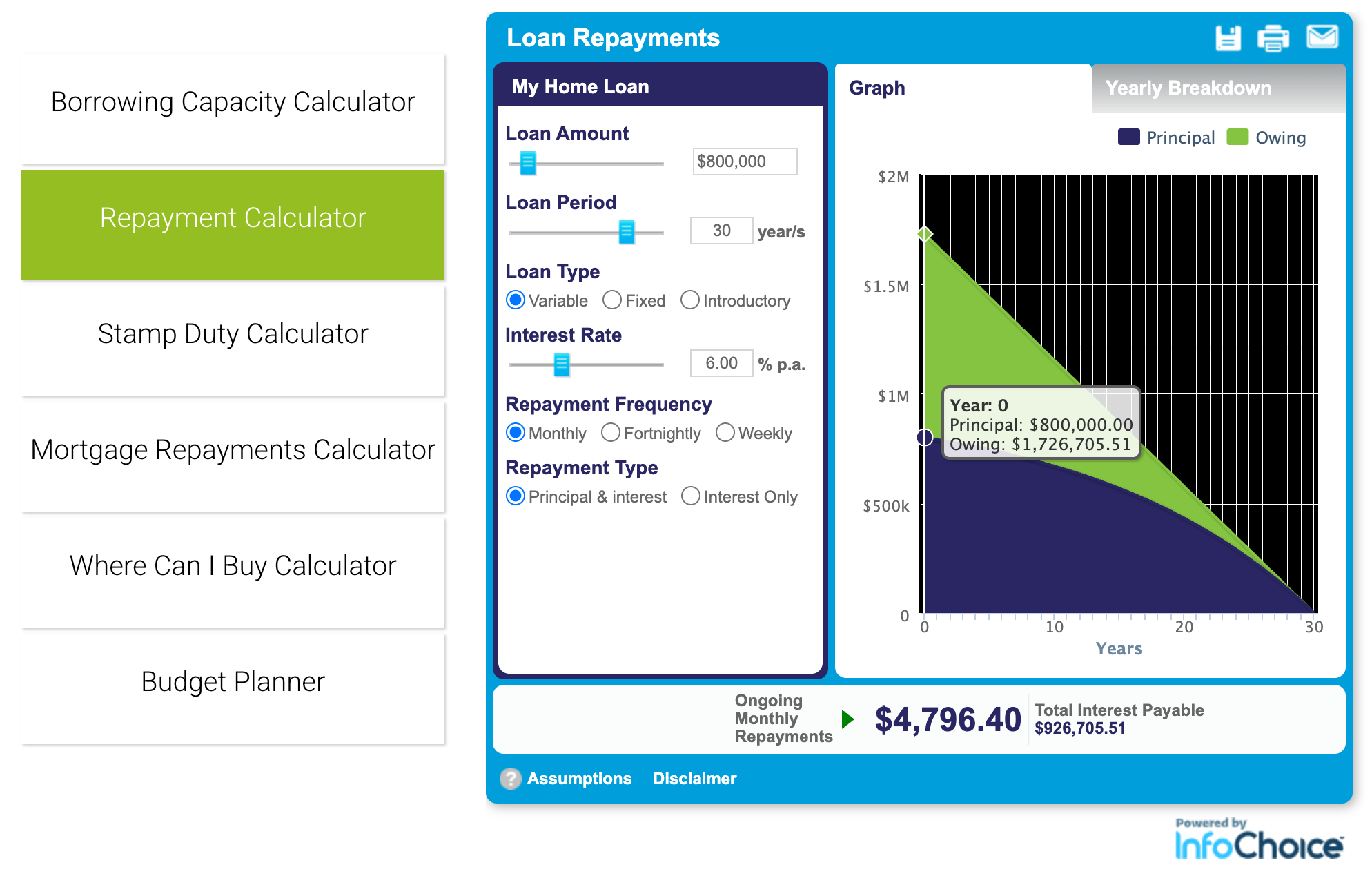

With the 30 years time horizon, the question of affordability shifted from “how can I come up with $1,000,000 to buy a property?” into “how can I come up with $4,613 every month to pay for it (over the next 30 years)?”

Suddenly, it all seems a lot more achievable.

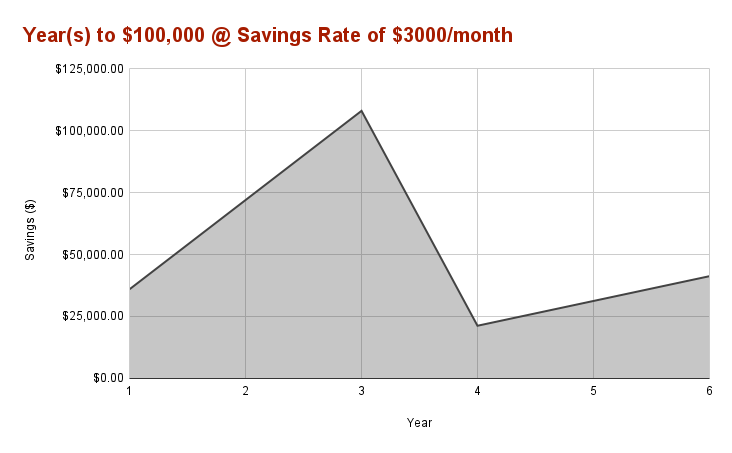

Plus, what you lose in cash flow, has now been traded for a potential for leveraged capital gains from owning a property, which hasn't been included in the Years to $200,000 chart since we're not talking about paper gains.

While it is a coincidence that the current market equilibrium is such that one needs 10—20 working years to save for a deposit, with an instrument that gives one 30 working years to pay it off, but one cannot help but think that this is the implied life script for the everyday persons.

Residential property loans can go for as long as 30 years, but you’ll find that, as you age, mortgages are harder and harder to come by and if they do, the amount will be lower and it has to be repaid in ~5—10 years.

Someone who is 70 is statistically less likely to live for another 30 years than a 30-year-old. That’s a fact of life.

A 70-year-old is also less likely to have as strong an income to service the mortgage than a young, healthy working-age person.

Why not 20, then? Well, because most people whose source of down payment is through employment, wouldn’t have worked long enough to have saved an adequate amount of deposit, or climbed high enough to qualify for $1M loans. However, being young is not a penalty when it comes to getting a loan, unlike old age is.

As long as you can come up with enough equity and loan amount to add up to the price of the asset, you, too, can buy a $5M property at 20.

The Ideal Lender

Lenders are divided in to “tiers”: tier 1 being the big 4 banks, tier 2 the regional banks, neobanks and credit unions, tier 3 being non-bank institutional lenders, and tier 4 being private capital. This means nothing to the first home buyer, as a loan is a loan... right?

Everyone wants the lowest interest rate. A subset of it are the people who want, or have to, get the biggest loan. The more paranoid of the bunch would also want a lender that's won't go bust anytime soon, fearing of being asked to pay the full amount before the 30 years is up. You can have it all, just not at the same time.

At the heart of it is the question: what is affordable?

Is affordability measured by the shortest time to get into a property? If so, you'd want the least amount of deposit to save up for, in exchange of paying higher interest overall. Less down payment required means it's more affordable upfront, at the cost of paying higher interests and bank fees overall.

While it might not be the cheapest, saving up $100,000 to buy a $1,000,000 property with 90% LVR, for example, can be more affordable than another 5 years of battling inflation to save up to a $200,000 down payment, only to find out that the same property is now priced at $1,200,000.

The closer you are to being the ideal borrower, the more likely you can get the most amount of loan from the tier 1 lenders. After all, only they can lend up to 95% the purchase price, for a fee.

If affordability is measured by the lowest burden on your cash flow each month, you'd chase the lowest interest rate, and this typically is afforded by paying more upfront and paying down loan as quick and as often as you can. In this scenario, affordable means that it's affordable ongoing.

Tier 2 lenders are neobanks and credit unions. Their USP is that they are leaner due to various cost savings, from a digital only presence, non-profit requirements, or a streamlined loan underwriting process. The tradeoff is that they usually can't afford as much risk, so they can't lend as much.

In the recent years, in a bid to take back the market share that went to tier 2 lenders, the big 4 banks have come up with their version of "lite loans", as the one I've worked on a few years ago. In order to create the cost savings, they removed the complicated package benefits and only lend up to 80% of the purchase price.

On a $1,000,000 property, this means that the additional criteria is having you figure out how to come up with $200,000+ down payment to qualify. On a $1,000,000 property, this means that the additional criteria is having you figure out how to come up with $200,000+ down payment to qualify. It's more affordable ongoing, but it's less affordable upfront for the first home buyer without a substantial capital backing.

Tier 3 lenders accomodate for more irregular incomes at the cost of paying higher interest compared to other types of lenders. This is because their business model is to finance the higher risk loans, such as equipment financing, bridge loans, and other time-sensitive turnaround 1—3 years projects, not a 30-year bond-like, stable home loans.

The banks of mum and dad are technically tier 4 lenders, which lend to an even smaller, even more specific pool of applicants.

What if I don’t have enough savings for the down payment?

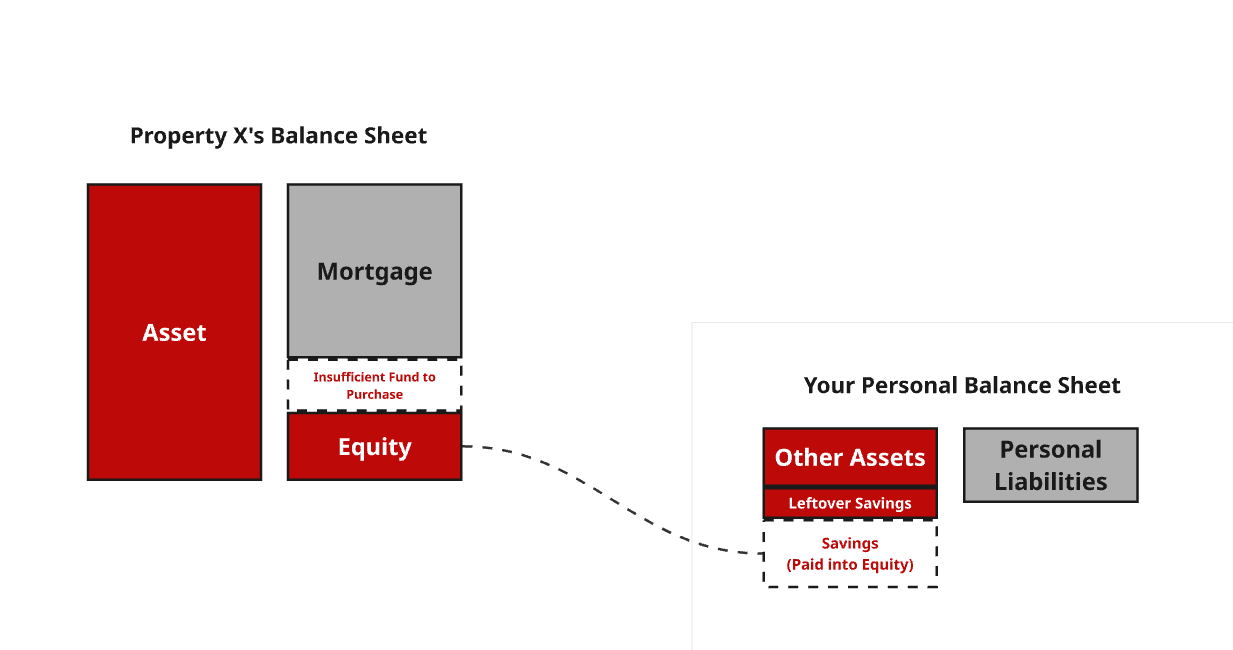

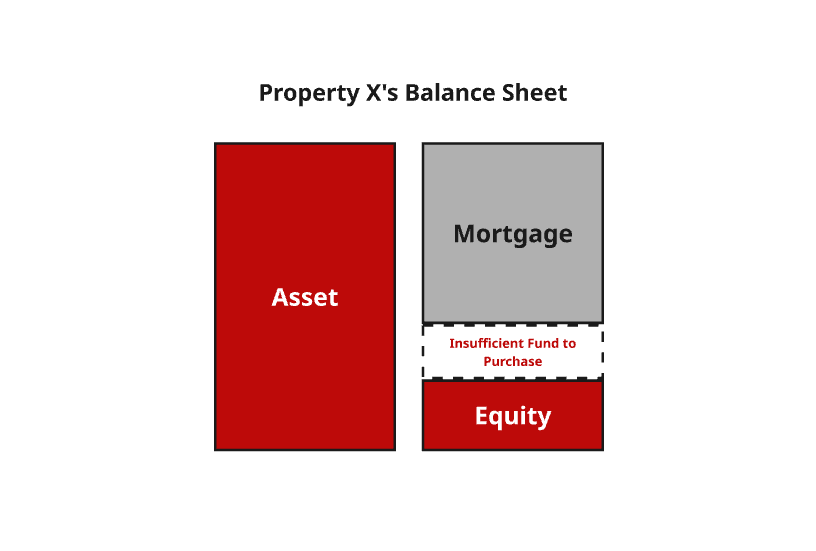

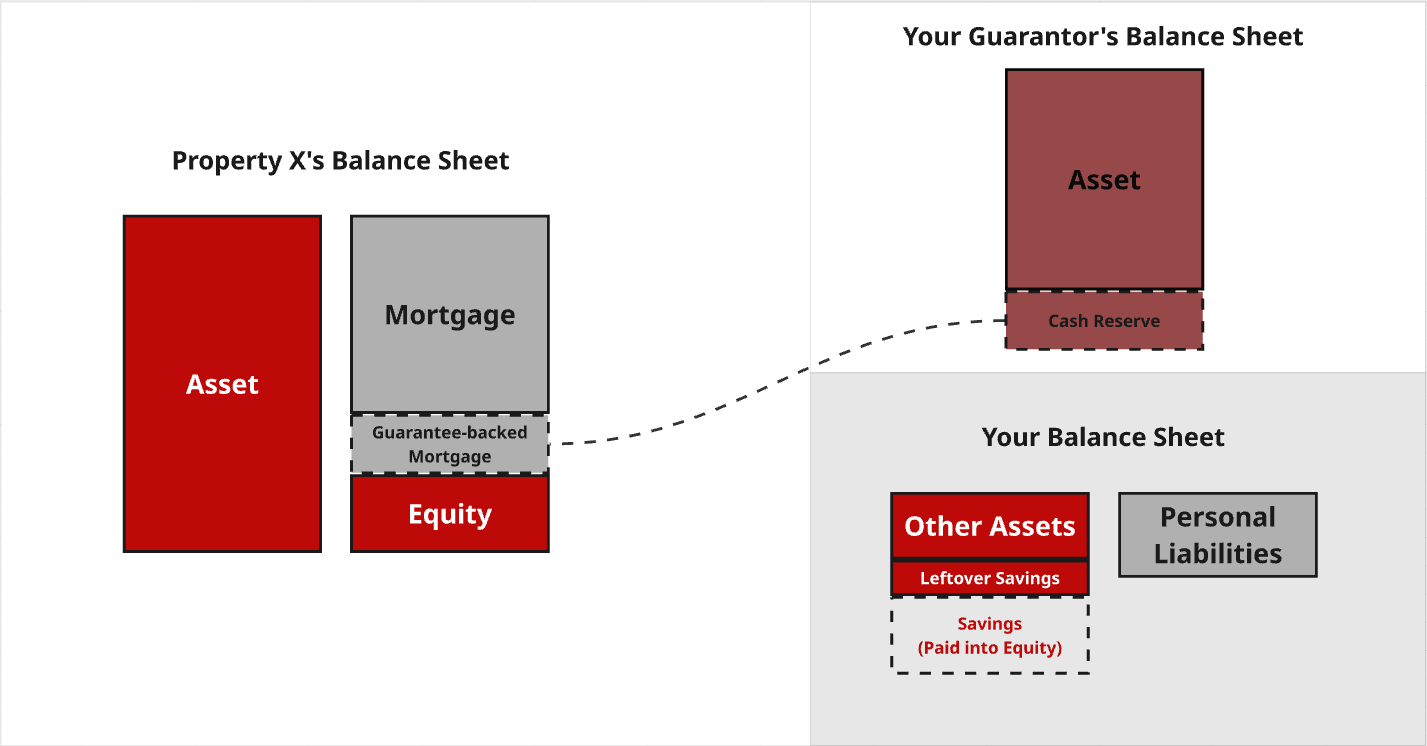

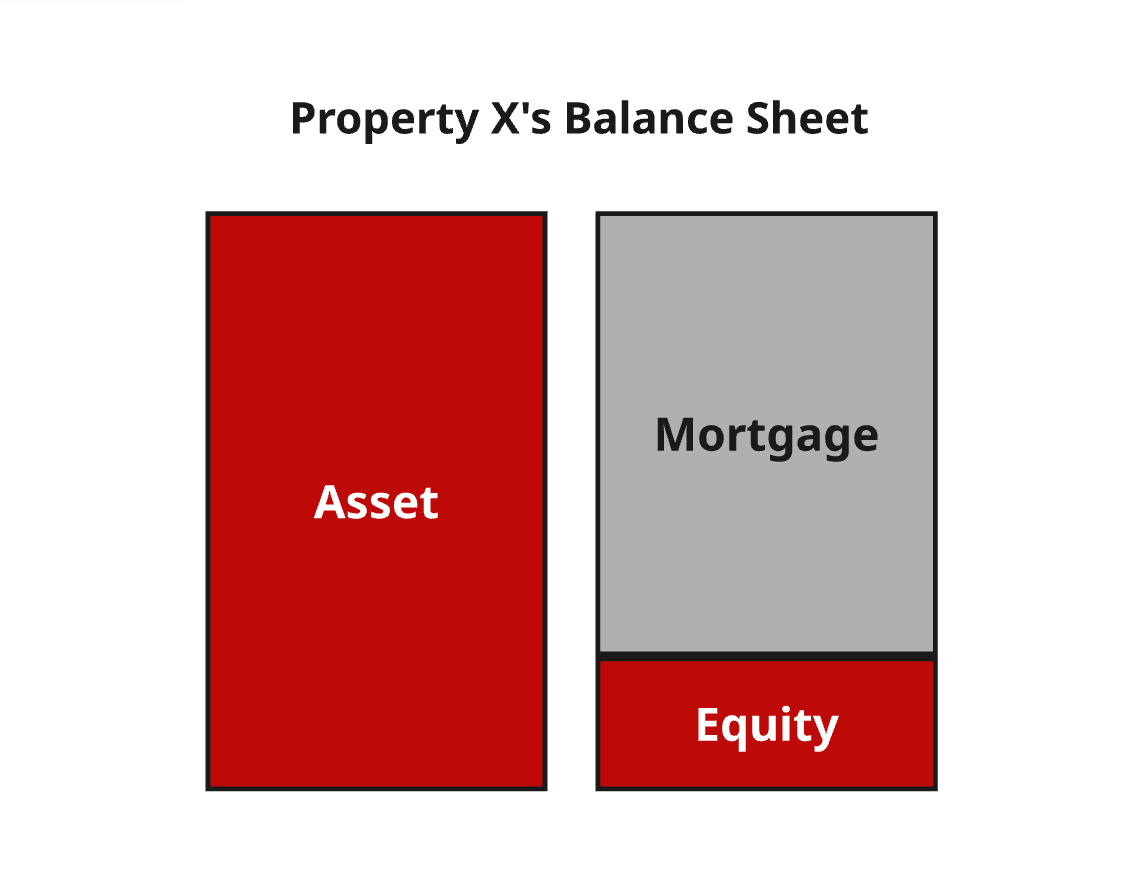

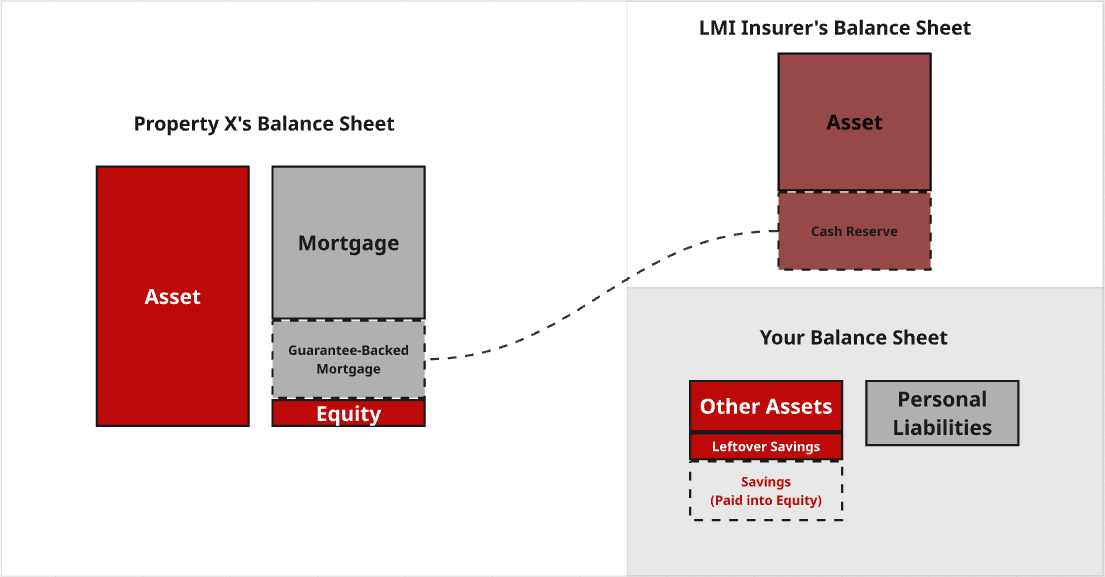

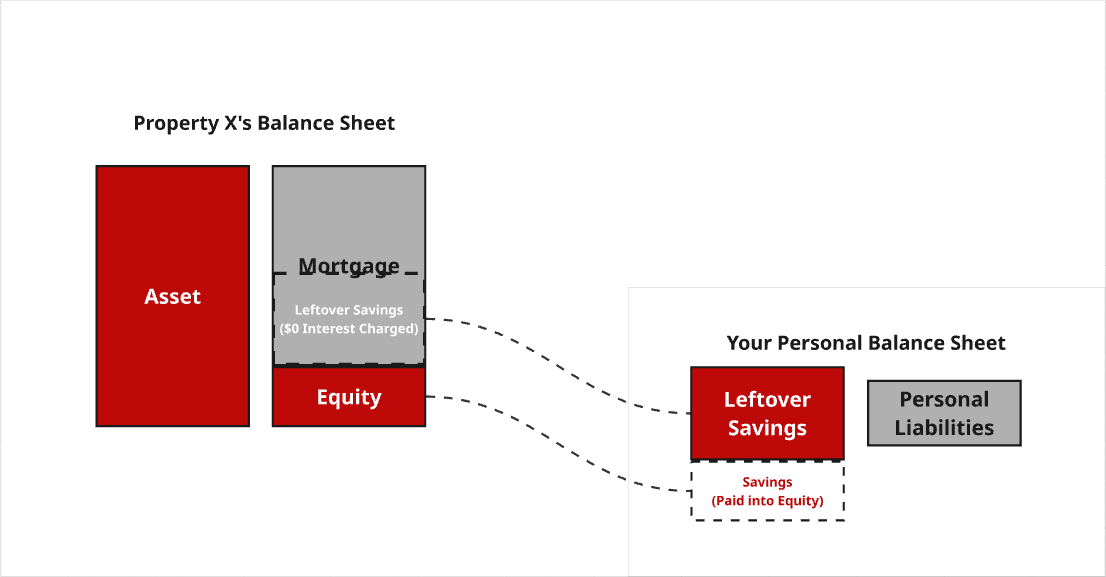

When you buy a property, you essentially convert your savings into the property's starting equity, on its own balance sheet.

You bridge most of the shortfall with the mortgage. If the amount still doesn't balance out, you cut costs, lower the price with subsidy, or get try to get more funding some other ways.

You have 3 options:

- pay with more time and energy to build up your savings

- pay with more energy and social capital to jump through the hoops and apply for the privilege of a grant, or

- pay with your social/money capital and get a guarantor.

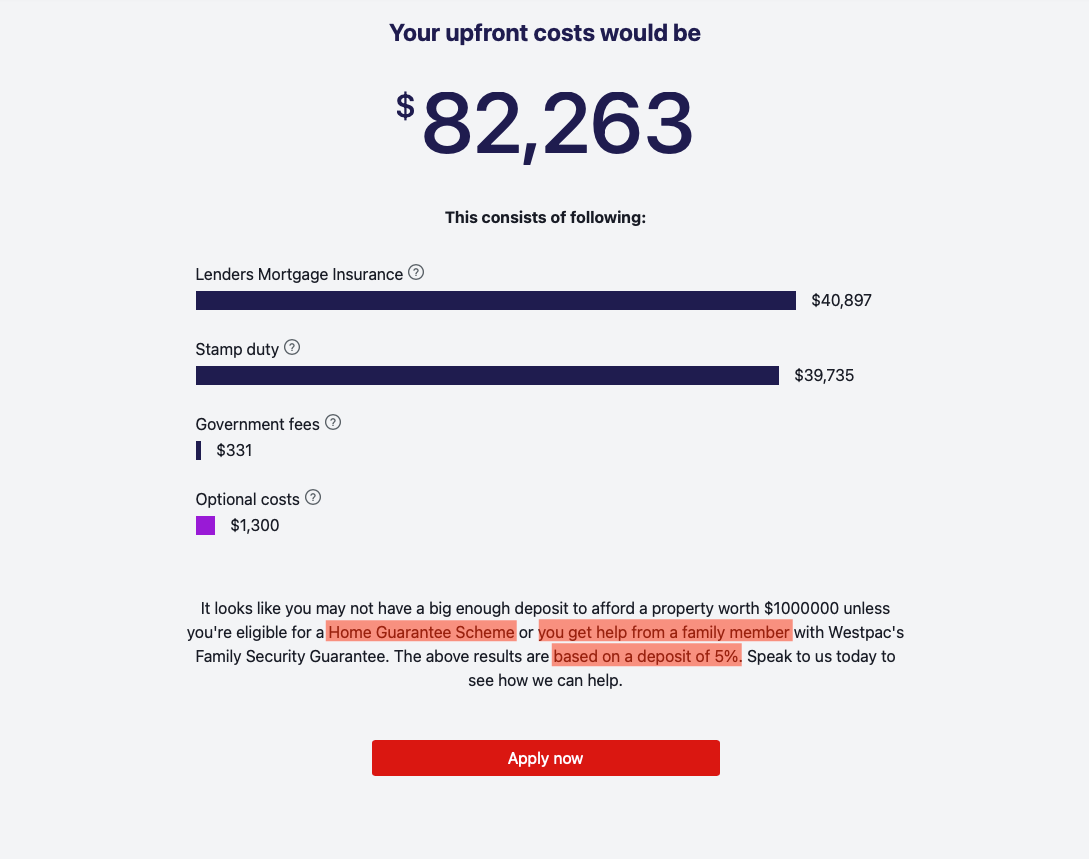

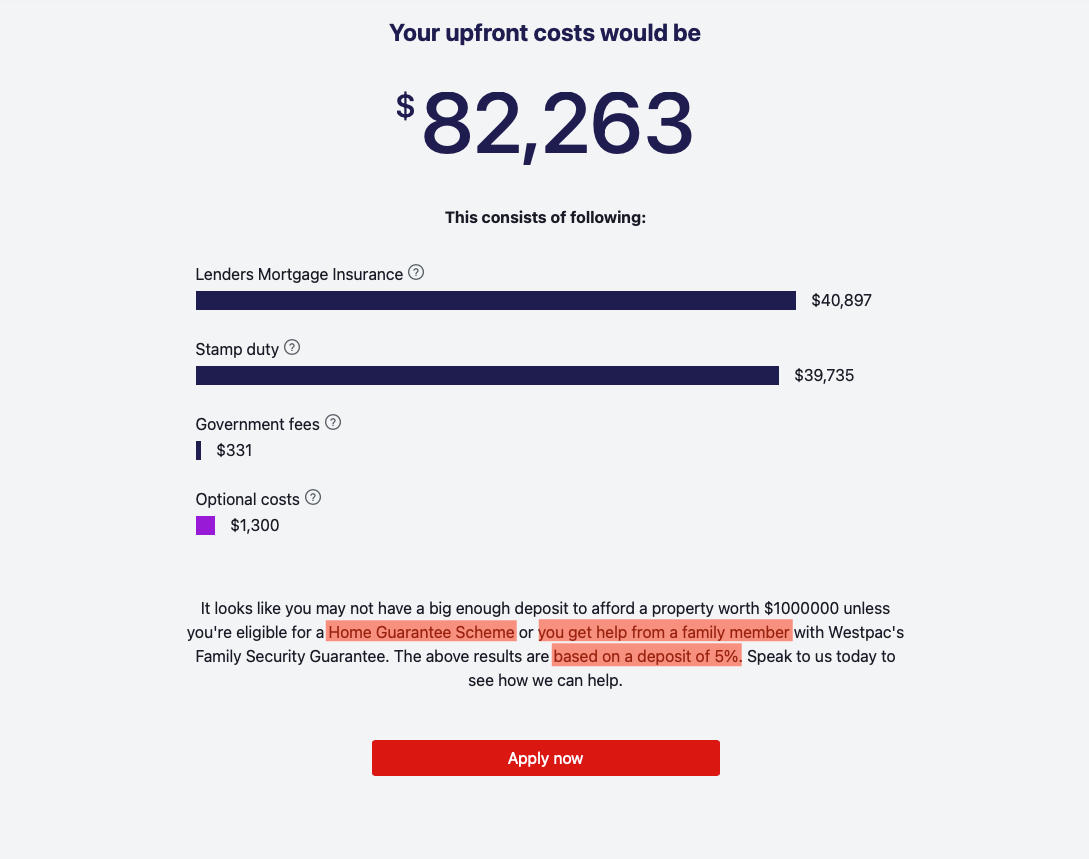

As this Westpac Stamp Duty and LMI Calculator not-so-subtly hinted, you might be able to still afford the loan if:

- you can get more money from your future self through some type of superannuation release

- you can get more money from your government, through grants and fee-exemption schemes

- you can get someone else to put their money up, usually a family member, as a guarantee so the bank is willing to lend more to you

- you can pay the Lender’s Mortgage Insurance to get an insurer to put their money up as a guarantee, so the bank is willing to lend more to you

- to total to a minimum of 5% deposit all up.

An Aside: Guarantors

Guarantors aren’t silver bullets; it is a scheme to increase your borrowing power, that answers the question of “what is cash-like, but is not cash?”

This, one would suspect, is the compromise that is made when a culture that promotes “a fair go”, meets the pressures of housing affordability and the political correctness of keeping house prices up. No one’s giving any free money, but every bit still helps some to get ahead.

You can think of guarantors as the providers of “shadow” equity. It guarantees a part of the loan that’s normally assessed as unaffordable based on your financial circumstances alone, but is now considered safe enough to lend, because the gap can recouped from someone else if you stop repaying.

Where there used to be a gap between what you want to buy and what your cash + loan can afford:

In the meantime, the bank will now lend you that amount, and you will pay interest on that amount, like a normal loan.

In other words, the more collaterals the lender can get, the more likely the bank deems you safe enough to lend, thus lend more to you.

A Lenders’ Mortgage Insurance, or LMI, is technically a corporate guarantor that also serves to stretch your affordability, whom you pay with money-capital instead of social-capital. More of that in its own section below.

What if I can’t borrow enough for the property I’m after?

Find a better paying job, buy with more people, adjust your expectations in terms of what you want to buy, and don't forget to advocate for affordable housing.

As individuals, we can do the first three. But it does no good for the society, if the only solution is that everyone should learn to run faster, if they had missed the train.

We will discuss more about how a banks decide how much to lend you in the Serviceability section below.

The Terms of the Mortgage

A mortgage, at its core, is a business contract between you and the bank. There’s a give and take that happens, sealed with an agreement at the end.

It doesn’t feel like one, because:

a) the average homebuyer is neither familiar with doing business nor contracts,

b) bargaining has all but disappeared from our everyday transactions, and

c) the terms are generally about the same between lenders of the same calibre, so that

d) there’s not much you could do to negotiate the terms, besides going to another lender offering a bigger loan, better interest rate, or other perks.

With its high desirability, combined with the lack of experience on the applicant's side, it would’ve been very easy for the banks to create imbalanced contract terms. However the regulators are also aware of this dynamic, and had throughout the years put in a lot of regulations in favour of the people. This is why most mortgage terms are fairly standard and with a lot of leniency compared to other types loan contracts.

What this means is that while there is little room for negotiation, said guardrails also make mortgages comprehensive to the everyday persons without too much power imbalance.

To get a mortgage, there are two main things to pay attention to: Loan-to-Value Ratio (LVR) and Serviceability.

Remember these fundamental assumptions in finance?

- Volatility is risk.

- Stability is safe.

Sometime in history, some persons came up with a way of putting a price on risk, leading to the creation of insurances and its eventual adoption by the mortgage industry.

And so in the language of money, contracts, it becomes:

- Risky pays more.

- Safe pays less.

The less skin one party has in the game, the more tipped the terms are in favour of the other side, as a way to put a price on risk. This is the story of LVR.

Loan to Value Ratio (LVR)

How much you put down doesn’t decide how much you can borrow.

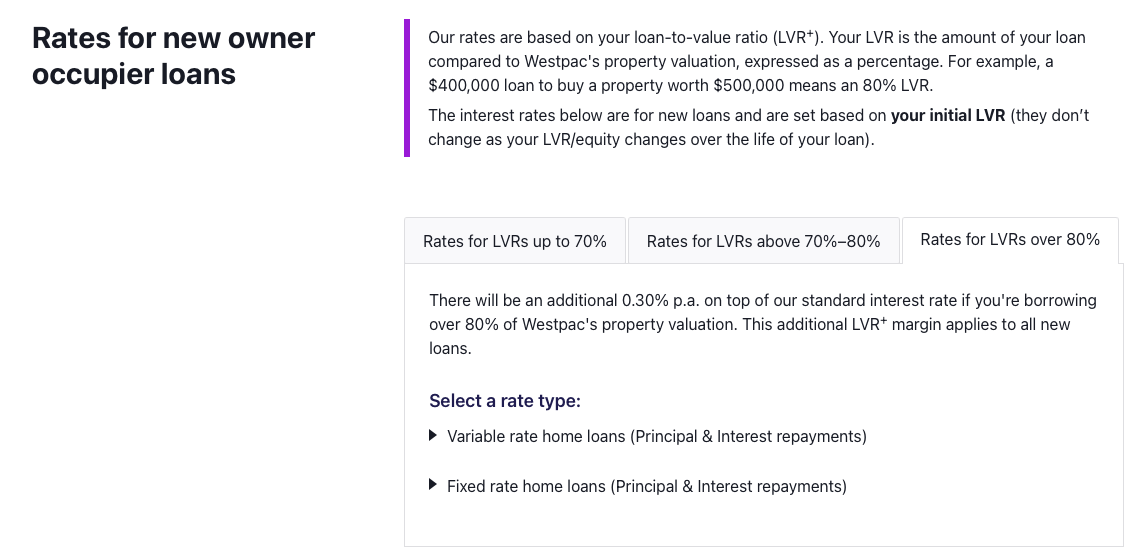

How much you put down does decide if the bank will lend to you at what interest rate, because they have a business rule that calls for a hard limit to what LVR ratio they will or will not lend.

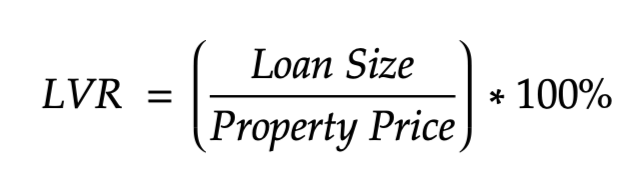

LVR looks at the value of the collateral which, in this case, is the property.

To you, the property is an asset that you can control at anytime, but to the bank, it’s a collateral, meaning that they can only control — taking over and selling it, usually — if you break the contract. They refer to the same thing from the different stages of a contract.

Imagine yourself lending money to someone to buy a $1,000 TV. They sign a contract, allowing you to sell the TV if they miss even 1 repayment. Would you give them $1,000? Not if you think like a business! On top of the $1,000, remember that there’s still the money, time, and energy that you need to spend in order to sell the TV.

The established golden ratio for LVR is 80%. For mainstream banks, this is the point that’s deemed as the “safe leverage ratio”, according a combination of regulations, business rules, and skin-in-the-game theory of accountability.

Any more than that is deemed as “too risky to lend to”.

The risk that a hard LVR limit tries to address is that without enough skin in the game, people would not take it as seriously, leading to people abandoning their loans more often (defaulting).

That tipping point is set to be 80% LVR, and any gap above that has to be bridged by extra guarantees, or by more cash from your side.

It looks at your property’s balance sheet:

LVR, in essence, asks if you can put enough skin in the game for them to lend to you.

To afford higher priced property, come up with a bigger deposit.

…except that that’s not entirely true, because banks can now still lend at > 80% LVR, for an additional price.

Are you familiar with the Nudge theory?

Because banks are businesses, it is safe to assume that they want to make more money. When you sell a loan product, this is done in 3 ways: a bigger loan, a higher interest rate on the loan, or allowing more people take out loans.

Since they can’t bump up the interest rate too much before people refinance away, that leaves the other 2 ways to nudge potential borrowers: higher loan and allowing more people to afford the loan.

To have more people take out loans, technically there are only 3 ways to do so: be able to save and earn more to qualify for a 80% LVR loan, have more properties priced to a level affordable by more people, or be allowed to borrow more.

The first and the second way are outside of the lender's control. But the third way…

This is how Lenders’ Mortgage Insurance was born: a way to allow people to borrow more and have more people borrow more. You don't have to take it, but it's there if you wish to.

An Aside: Lenders’ Mortgage Insurance (LMI)

A common confusion regarding LMI is “what and who does it cover?” The answer is: the lender, and the lender. Your role is to pay for the privilege of a guarantee.

An LMI is the commercial answer to "what is not cash, but is cash-like, that could bring the LVR risk back down to a 80% LVR level?" the answer is: insurance.

A 80% LVR is a non-negotiable, acceptable risk-reward for a home loan as a product. When a bank lends up to a 95% LVR, it's done so in the way that the risk has been paid down to a level that's equivalent to a 80% LVR loan.

Similar to a family guarantee, an LMI means that someone else is putting up their money as a collateral, that can be paid to the bank in the case that you stop repaying. Cash-like, but is not cash. Since you and the insurer doesn’t have a longstanding relationship and goodwill, however, they ask you to pay in dollars for the bigger money guarantee.

Remember this screenshot from Westpac’s Stamp Duty Calculator?

In this extreme example of a 5% deposit, priced at an eye-watering $40,897, LMI surpasses even Stamp Duty as the biggest purchase cost.

What do you get in return?

Well, with a $1,000,000 property at 95% LVR, you pay the insurer $40,897 for the privilege to unlock a guarantee of (95% - 80%) * $1,000,000 = $150,000 to bring it down to a 80% LVR.

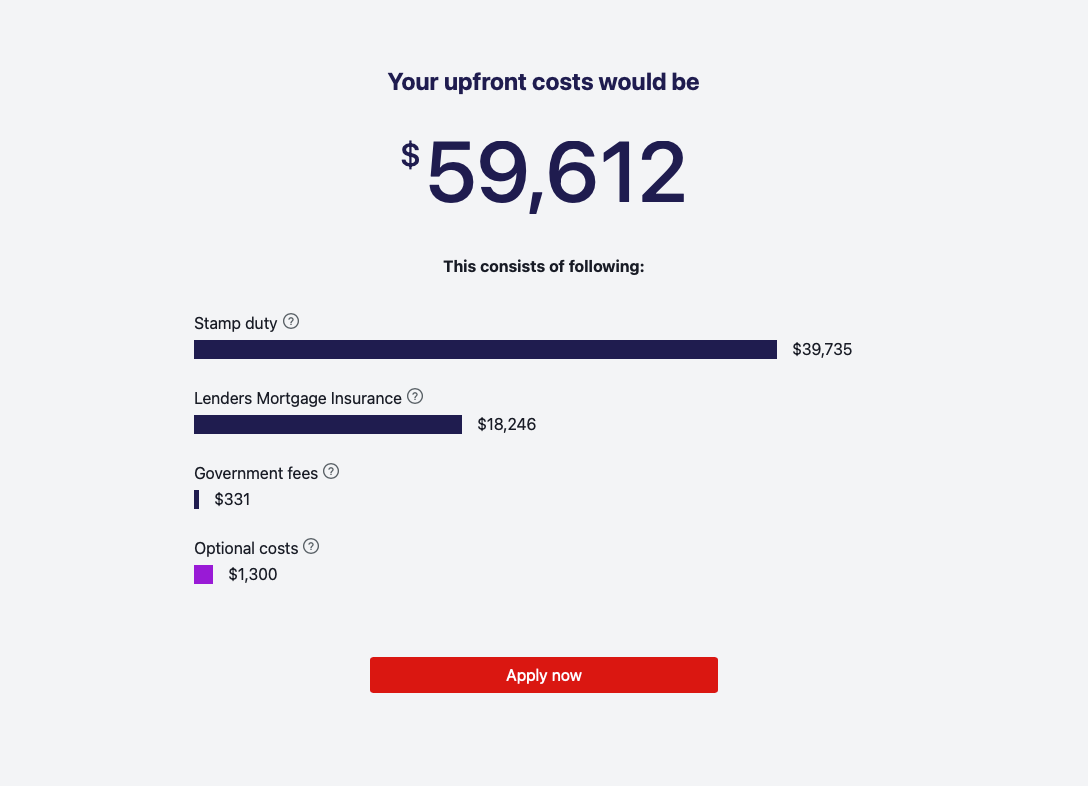

If you have $150,000 in savings instead, the LMI goes down to $18,246, because you effectively have 10.86% deposit.

After the upfront costs, the amount of equity that you have is ($150,000 - $39,735 - $331 - $1,300) = $108,634 = 10.86% of $1,000,000, or a LVR of 89.14%.

The amount that the insurer has to cover to fill the gap between the current LVR, 89.14%, and the ideal 80% LVR is 9.14%, so in dollar amount it is (89.14% - 80%) * $1,000,000 = $91,400.

If you have a family member that’s willing to put up their asset as a guarantee, consider giving something nicer than a pack of beer as a thank-you, since they just saved you the equivalent to 10 — 20 iPad Pros.

A $40,897 LMI, however, can still be more affordable than a $39,735 Stamp Duty.

How is that possible?

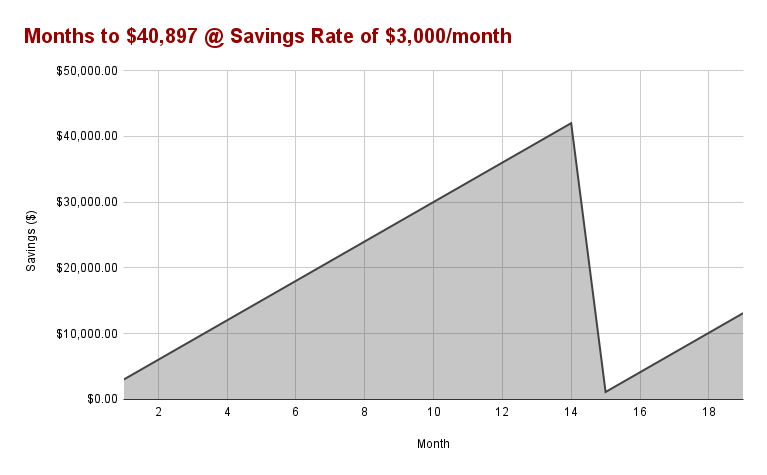

Unlike Stamp Duty, which has to be paid upfront, the nudge is that LMI can be capitalised, meaning that it can absorbed as part of the mortgage to be paid over 30 years, changing the conversation from upfront capital into cash flow.

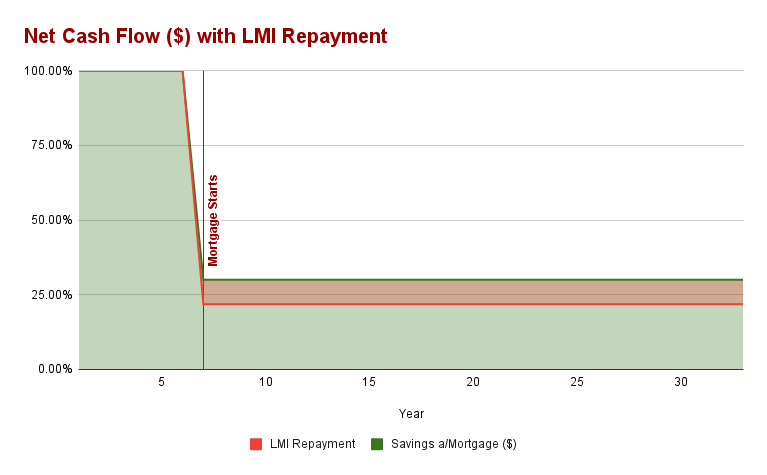

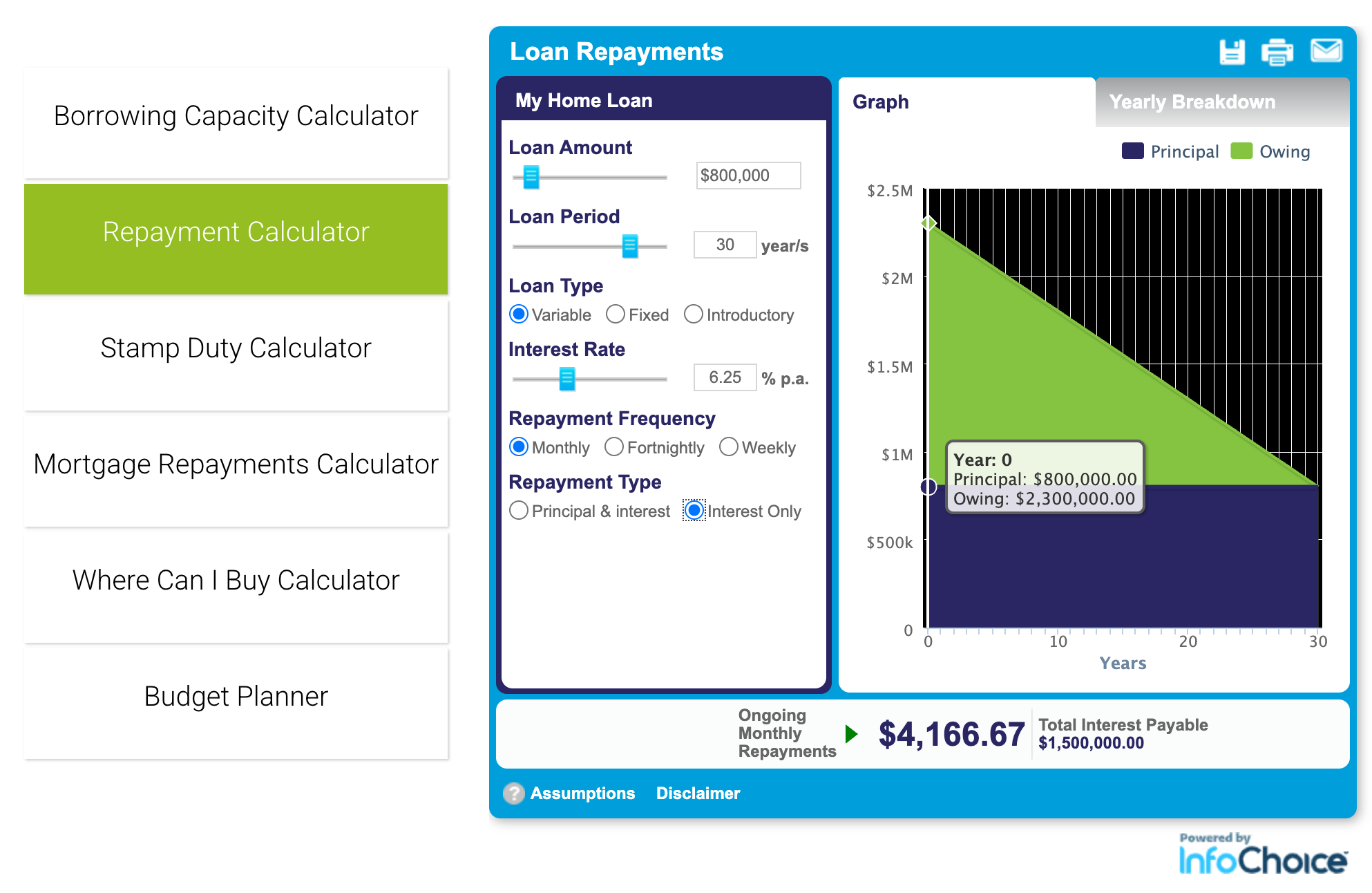

Just like how 30-years mortgage changes the conversation from $800,000 into $4,613 every month for the next 30 years, instead of having $40,897 taken out as a chunk off of your cash at the start:

A capitalised LMI is changed into $204.49 interest + $40.71 principal every month, for the next 30 years:

With enough time, affordability can be stretched as far as people’s cash flow can go.

Optimising for LVR

Because LVR is about hard cash vs loan size, the only thing you can optimise, in order to pay the least fee and get the cheapest interest rate, is to buy with as much cash as possible, with the lowest amount of debt.

Serviceability

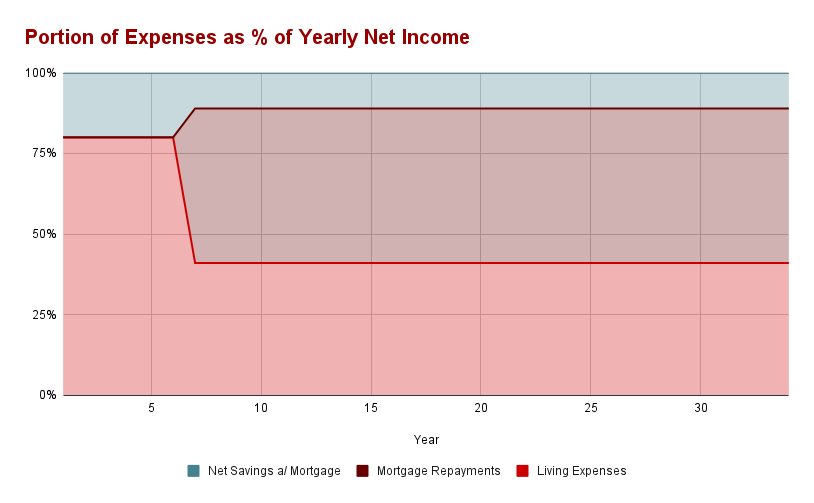

Serviceability looks at your cash flow. This is the portion that will be locked into repaying the loan, that affects your day-to-day directly, and it looks at the risk that your other expenses will eat into the amount that you can pay into your mortgage.

Just as there is a hard business rule about having no more than 80% LVR as the "safe amount" to lend in relation to the property price, there is another business rule that sets the "safe amount" of 30—35% debt repayment-to-cash flow ratio.

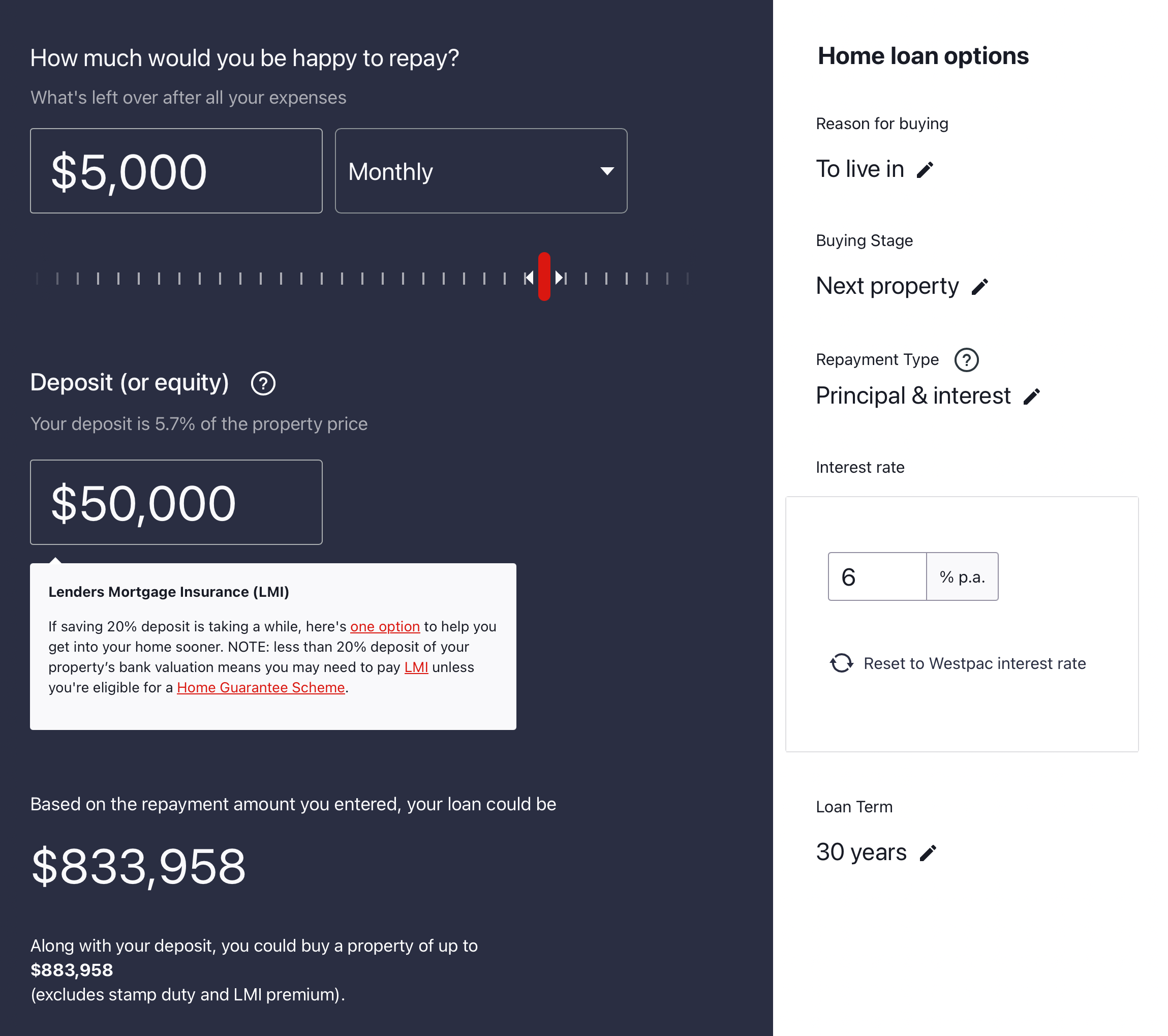

When you see a reverse mortgage repayment calculator like this, what it essentially does is assume the amount you entered and reverse-calculated it back to 30 years, to come to the amount that can be lent safely under this business rule.

The strength of your cash flow dictates how much you can borrow. The higher your free cash flow is, the more you can borrow. As such, anything that might regularly compromise your cash flow, becomes the biggest concern to the bank.

This logic works on the upside too; anything that increases your cash flow on the regular, increases how much you can borrow. With the way the Sydney property market is going, combined with the lack of opportunity to increase income in other ways, it’s only a matter of time until we see property-backed poly relationships to service a Sydney property.

What is not standardised across lenders is what type of income counts as regular cash flow, mostly on the income side, which is why some can lend more or less if you have a lot of non-base, regular incomes, such as overtimes if you work on a casual/part-time basis, or if you are in an industry that pays a lot of bonuses and benefits instead of a high base salary.

Here is where a mortgage broker is worth their weight in gold, because without a broker, you’d have to contact the lenders directly yourself to compare all these. The more you deviate away from the ideal borrower profile of a high-base-salary, stable full-time employed borrower, the more variations you can expect in what the potential lenders will lend to you.

Serviceability Modifiers: Income Side

Oversimplified, net income modifiers go as follows:

- 100% * base income

- 0—80% * overtimes, bonuses, commissions, benefits

- 75—100% * rental income

- ...and a plethora of other weightings for business and investment incomes.

While this can be seen as form of penalty, this is mostly as part of the government regulation to build in your margin of safety, as a guard against underreporting and under-risk managing, such as inflation. As the result, you can borrow less, and it also means that it's less draining on your cash flow by default.

What it implicitly says as well is that if you aren't comfortably employed with a regular base income, you ought to be able to earn a lot more to be able to afford the same loan.

Profit-only businesses, if left to its logical conclusion, would rather remove that margin of safety, because higher repayments means higher income when you’re sitting on the other side of the table.

Always remember: one party’s expense is another party’s income.

Serviceability Modifiers: Expenses Side

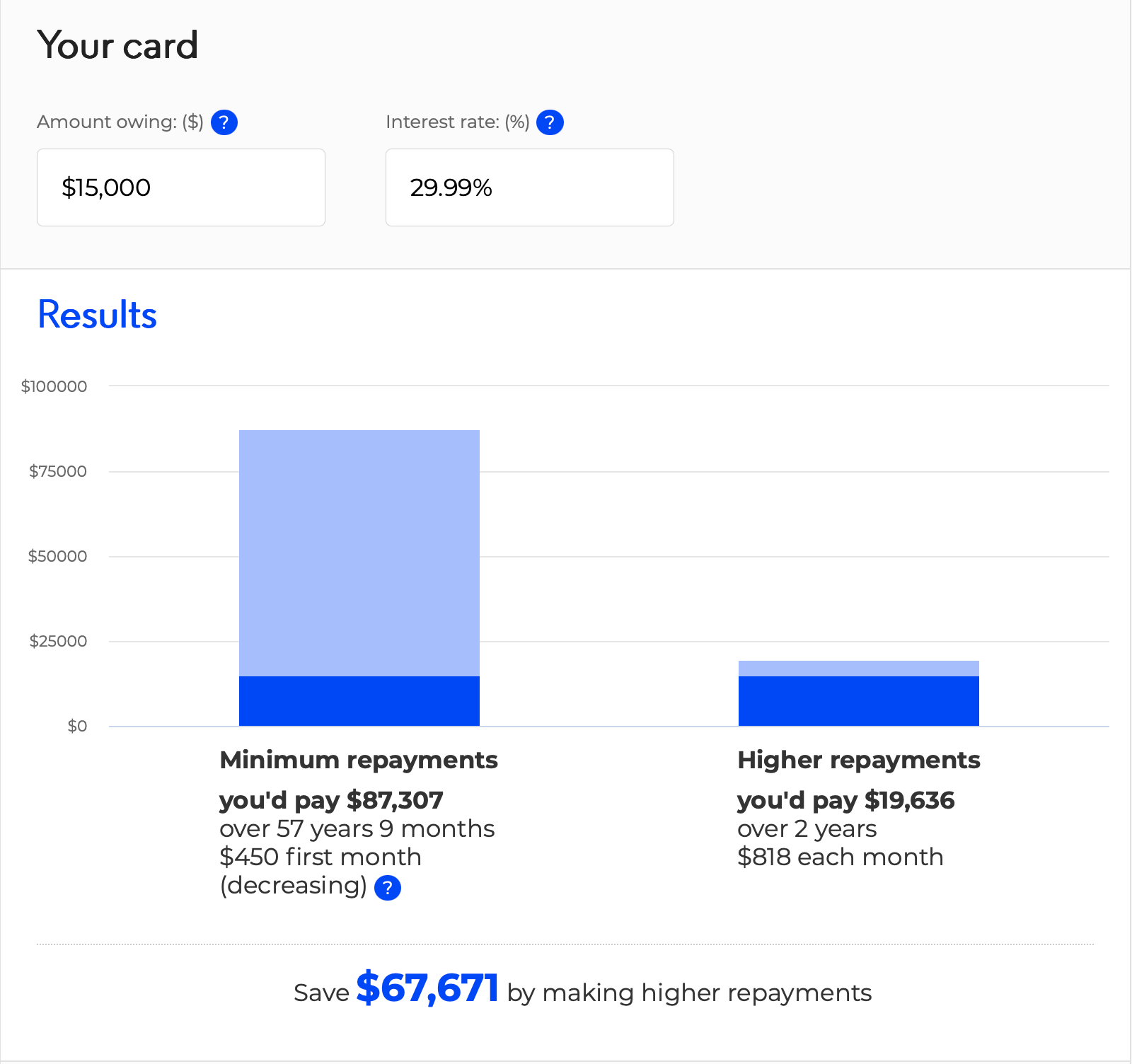

You might have heard that you should close down your credit card. Yes, that is essential, as a credit card is the perfect example of a competing, regular expense. Not only that the interest rates are a lot higher than the mortgage’s ~6% p.a. loan rate, incentivising the borrower to pay it first, but that said 12.99—29.99% also has to be paid each month without fail, which gets in the way of the mortgage’s desire to get paid first and to get paid the most.

That is why mortgage applications penalise credit card ownership quite heavily. By having one with a $15,000 limit, for example, even if you use $0/month, banks consider you as having maxed out your $15,000 credit card loan each month, reducing your cash flow by -$450, or a reduction of ~$67,000 on the total amount it's willing to lend to you.

They extrapolate it to 30 years of repaying $450 each month, because credit cards don’t have an end date. It only ends when you close it, so close it to soothe their minds. Nothing’s stopping you from opening it after you get a mortgage, if your credit card serviceability isn’t maxed out.

Different loans, different underwriting.

Optimising for Serviceability

Spend Less or Earn More?

Both. But if you can only choose one because you want to buy now, make increasing income your focus. Why?

Cutting your spend works, if you typically spend above the average. You have to be consistent for at least 3—6 months, because that's the length of time that the bank takes as your "typical spending pattern", in the bank statements you submit in the application.

As with any good lifestyle habits, this will take time to adjust, though it will benefit the rest of your life beyond the mortgage-getting phase.

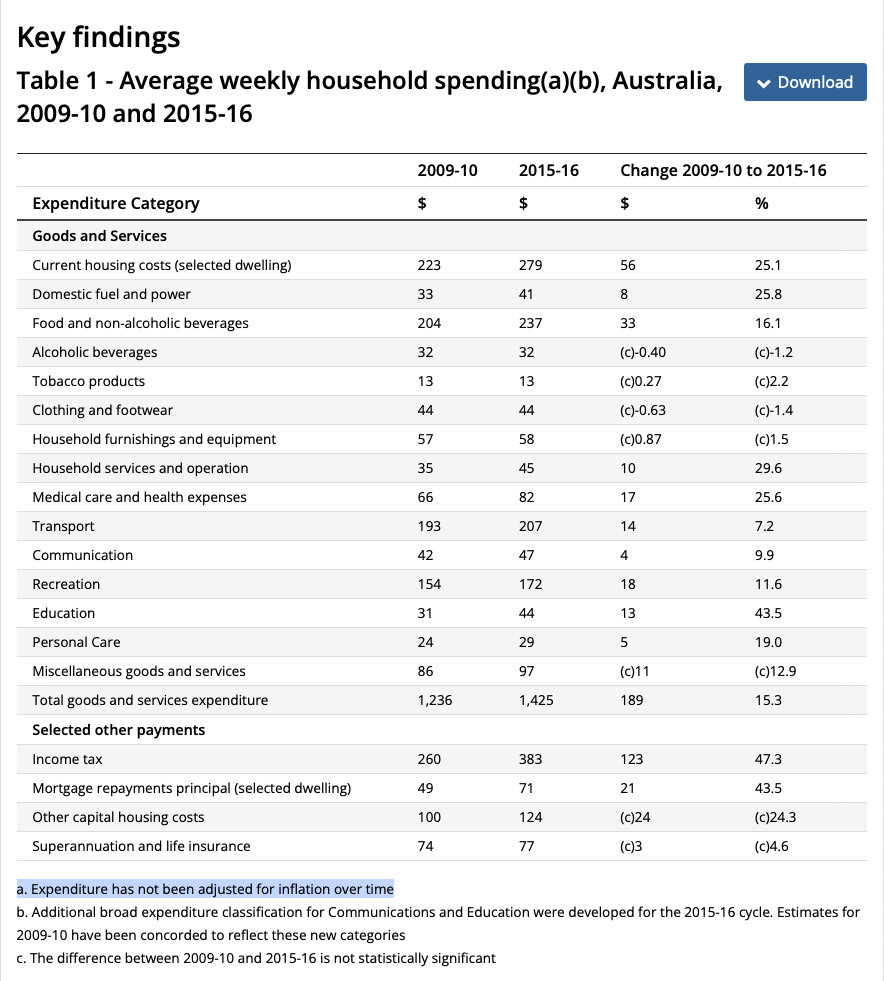

The second reason is that if you already live at or below average living costs, the bank will still take the population average (Household Expenditure Measure, or HEM) as your living costs instead of your actual one. The floor has a concrete bottom, but the glass ceiling is breakable.

Meanwhile, if you can manage to get a higher salary at a new job, you only need... a letter from your new employer (and 1 payslip potentially), to have your income assessed at the new base salary.

The reason no responsible financial advisors would push for this is that without developing a good money habit, expenses do tend to fill up the room that this extra cash flow creates, leading to a situation where your lifestyle technically can afford the loan in the beginning, but is brittle enough to break at the slightest inflationary forces.

An Aside: Fixed or variable?

From the borrower’s perspective, fixed = easier mortgage expense projections for the next 1—3 years. Variable = rates might go down, let’s ride the wave.

From the lender's perspective it is reversed. High chance of RBA cut = fixed rate < variable rate, betting that fixed rate > averaged RBA cuts over [the fixed rate period].

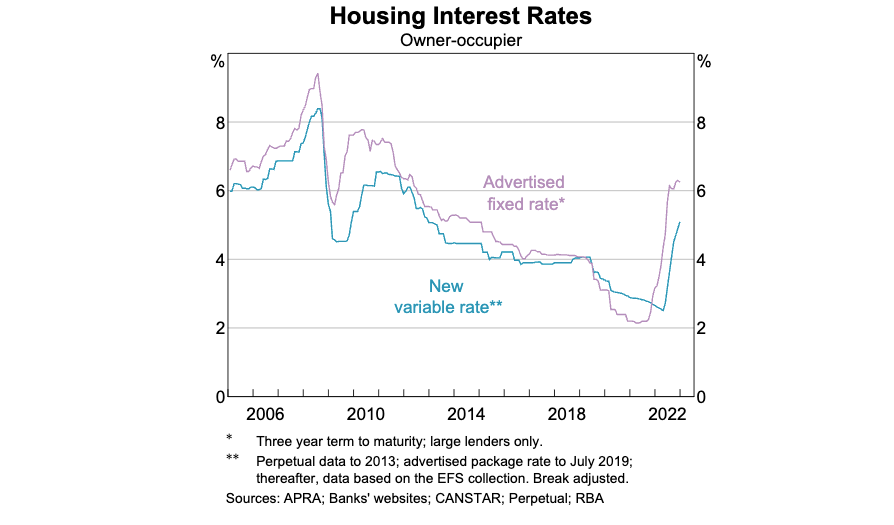

If the outlook is one of RBA rate increase, fixed rate > variable rate, as some might’ve seen at the end of the COVID lockdown period as the crisis was contained.

Without the ability to accurately predict the future, the question of whether to go fixed rate or variable rate is less about which one lets you pay the least amount of interest, than it is how much you value being able to predict your expenses.

Repayment Term: P&I, IO, or Offset?

Principal & Interest, or P&I, is what it says on the can. You pay interest and parts of the loan over time.

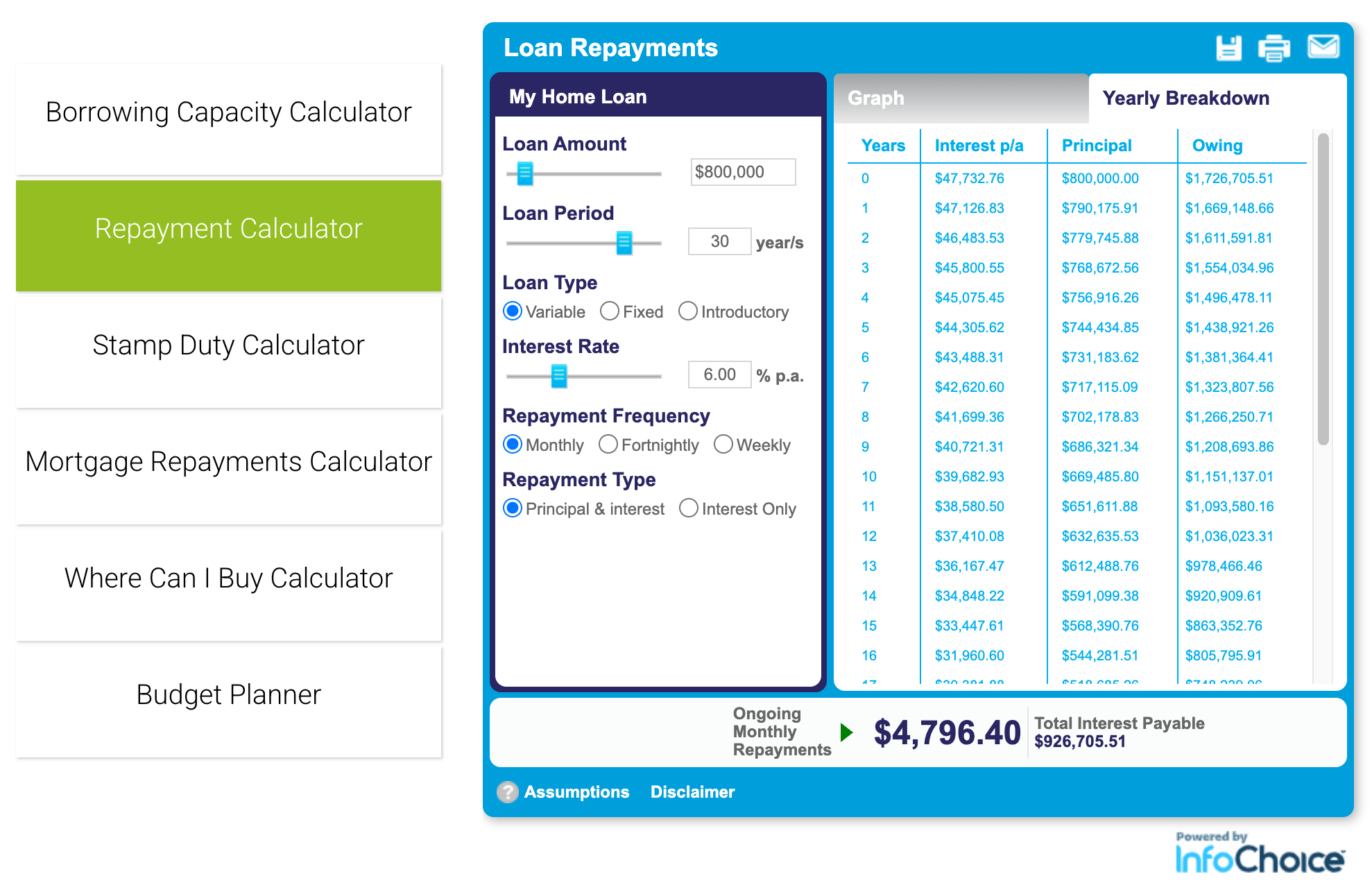

On a monthly repayment, you pay for the interest portion of starting with $800,000 * 6% / 12 = $4,000 in interest in the beginning, plus $796.40 into principal, paying down the loan.

The next month, ($800,000 - $796.30) * 6% / 12 = $3996.02 interest, plus $795.61 principal. So on and so forth… until the loan goes down to $0 at the end of 30 years.

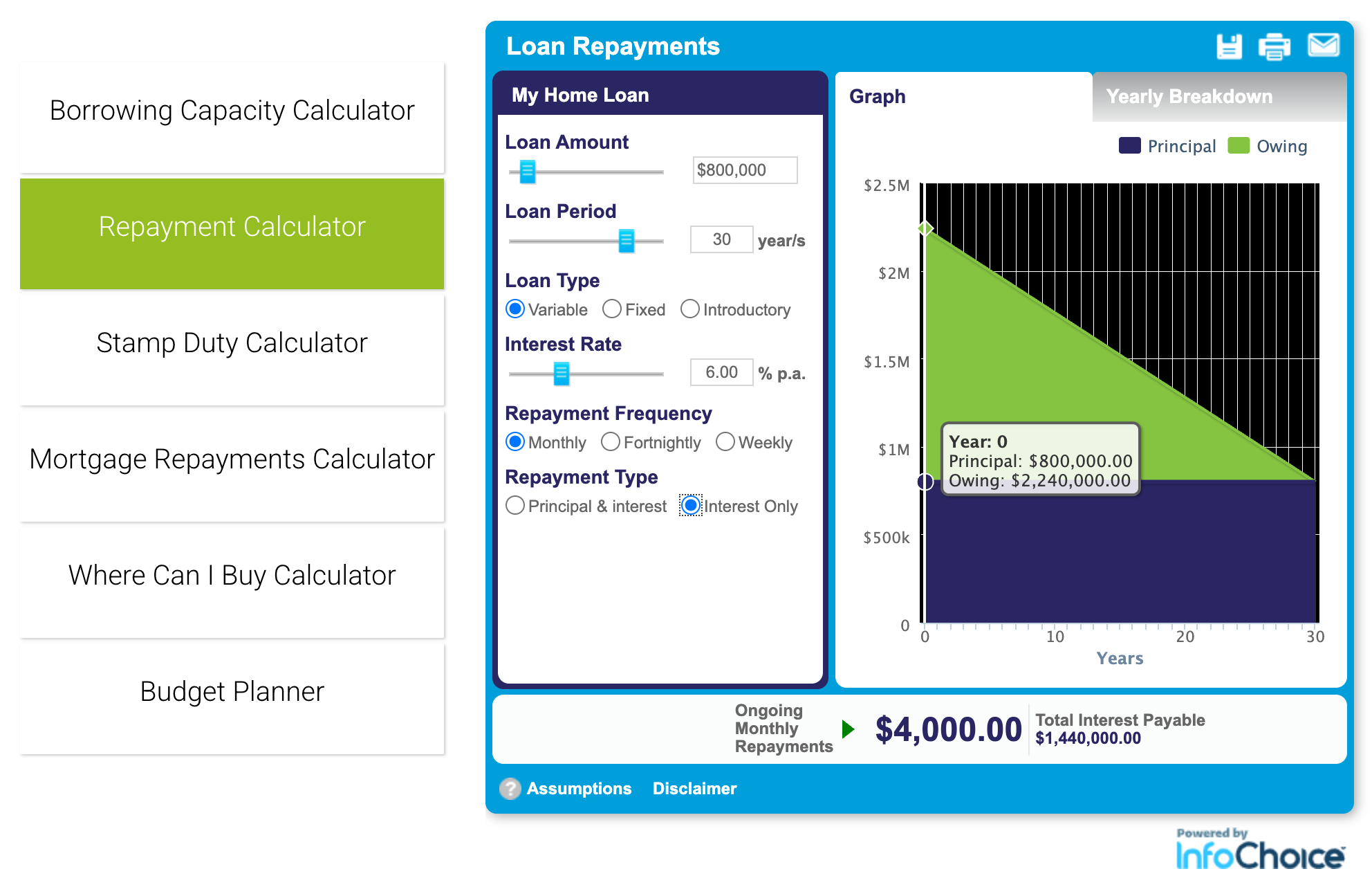

Interest Only, or IO, is P&I without the principal repayment part.

From the cash flow perspective, since you pay only the interest portion each month, the amount is lower overall. You pay $4,000 instead of $4,796.40, because you don’t pay down the $796.40. That’s +$796.40 back to your monthly cash flow.

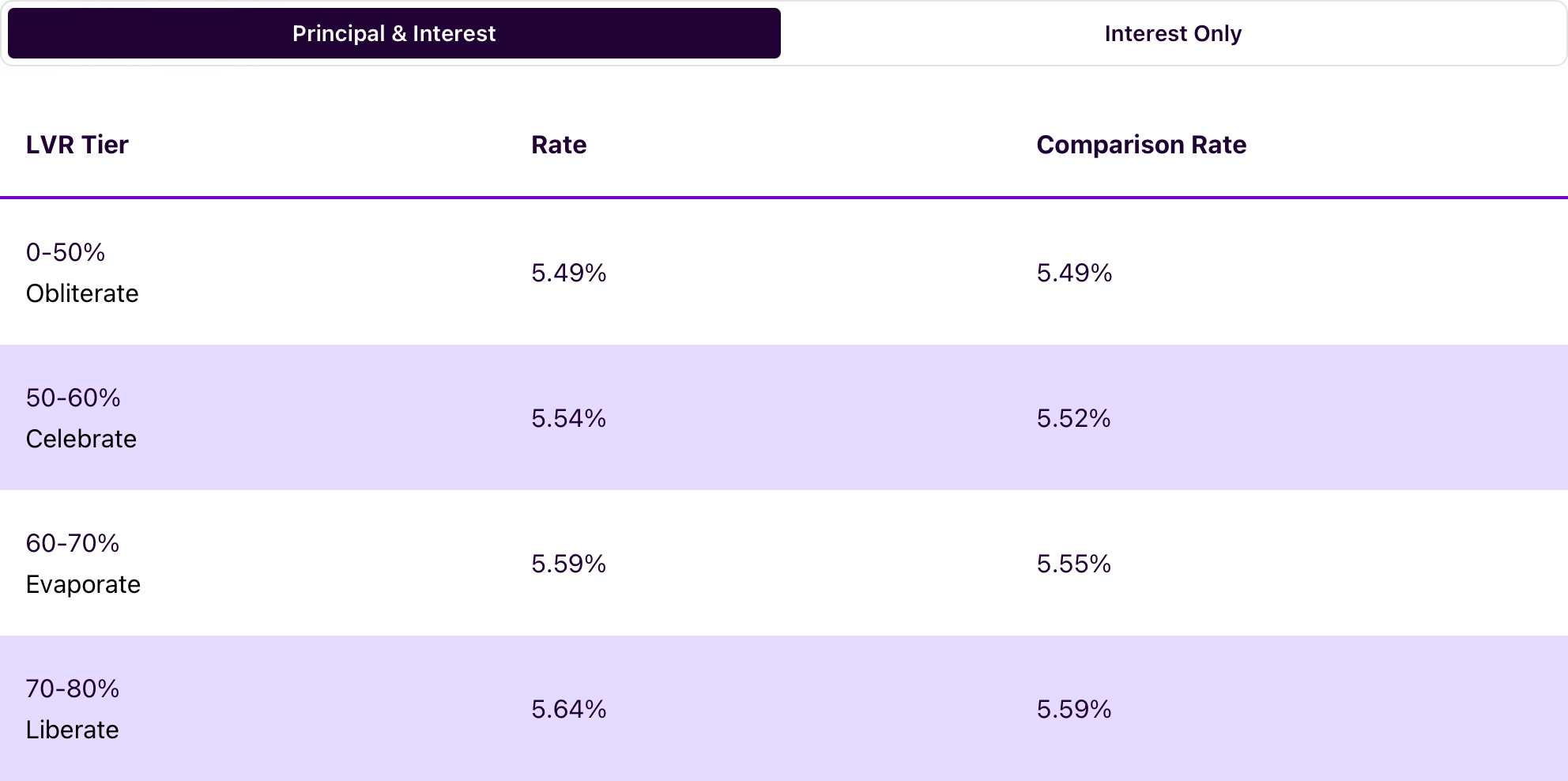

However, since banks are also aware that you can afford to pay a bit more, and that not paying down your debt poses as an additional risk due to less-skin-in-the-game considerations, realistically they tend to add ~0.25% to the advertised P&I rate to make up for the IO rate, bumping it up to $4,166.67:

People who choose the IO repayment type are after the most free cash possible, in exchange of paying more interest overall.

Why would anyone want to pay more interest?

Well, we did this to build our savings buffer back up. After putting the down payment, our savings were lower than what we were comfortable with, so we prioritised building it back up as quickly as possible.

Money now was more valuable than money later.

One can eat with money now, but never with money later.

Offset is not a type of repayment. It’s an extra feature that’s attached to a repayment type that lets you not pay interest on the amount of savings you put forward as an offset.

Just like a guarantor’s dollars, offset dollars can be thought of as a “shadow equity”. Only, instead of other people's cash, it's yours. In lieu of earning a monthly interest on your savings, you now save on interest on that amount offsetting the loan.

So yes, it is possible to have 100% offset and not pay any interest, if you accept that you won't get paid interest from the bank for your savings.

Some people do just that, for the ultimate liquidity. Other times it’s a way to park money and save on interest while waiting for another deals to be funded.

You typically pay a higher interest rate for the privilege, but this compromise allows you to enjoy a blend of P&I and IO repayments: save more on interest without locking away all your savings into paying down the loan.

Which type of repayment terms is "best" then? The shorthand to that is:

- P&I: if paying off mortgage is your only priority. Your cash flow will take the brunt of it, but over 30 years, you pay the least amount of interest.

- IO: if free cash flow is your priority. You pay more total interest compared to P&I, but you pay less cash ongoing.

You can always refinance to either type, as long as your net cash flow is strong enough for when the next lender assesses you.

Between LVR and Serviceability, the final figure a bank will lend will be the lowest one out of the two.

Mortgage, and a Life of One’s Own

With the size of a home loan being so large relative to most people's wealth, it naturally forms an expense gravity so great, that life tends to reshape around repaying the mortgage. If one's greatest pleasure in life is in the form of a domestic life lived in homeownership, that is an acceptable sacrifice that's worth the joy.

Anytime you deviate from the profile of the ideal borrower, this will pose a problem, if you still want to keep the home and needing to afford it with the help of a debt.

The obvious solution, then, is to pay down your home loan as soon as possible, or to sell up and be free from debt again. What they don’t tell you is that this costs 30 years of your life before you can truly live, if your life isn’t to be centered around servicing a mortgage.

Selling up and packing away is fine if you're committed to remain single for the rest of your life: your decisions, your consequences. That's the beauty of the single, less complicated, life.

If you have a family that counts on you being able to qualify for the home loan still, however, if you don't prepare for it, there will come a time where you can only choose 1: continue affording a family home, or the pursuit of a life of your choosing?

Without understanding the nuances of a loan contract, the responsible person defaults to serving the loan first at all cost, while joy gets the leftover budget, if any.

The irresponsible person, on the other hand, prioritises joy, while leaving the burden of a mortgage repayment to the rest of their family.

Neither of these appealed to me, as I don’t want a life of my own that’s built on the sacrifice of those whom I’ve chosen to become a part of it. So I chose the create the third way: to find a way to afford both, at the cost of having to figure out how to live the perilous life outside of a stable 9-5.

I made my resolve to understand contracts, for money has a language: its name is contracts.

And so can you.