Ah, property… the sure-thing you can talk about with anyone, the saving grace of everyone who’s not into footy.

While gold has achieved the mythical status as the safe haven, residential property, in Australia, has an even better reputation than gold. Good as gold is not as good as backed by bricks, when the dream that has evolved from a quarter-acre block and a hills hoist, is still very much alive in a 65-sqm place with a deck on which to BBQ on… a place to entertain your extended family come Christmas time, the very picture of a good, honest life — having “made it”.

It’s no small wonder, then, that with my early audience of 30-somethings, I’ve been asked about property 5—6 times (and counting) already, such that the intrusive thought of getting a licence and start charging did cross my mind. But I mustn’t get distracted.

Because I, too, am in want of more free time, instead of spending 2 hours with the next persons who's asking, I've compiled the common concerns in this post, with the focus on the financing side of things.

If you find it useful, please feel free to share this around. Follow-up questions welcome; I might compile it into a sequel, once there's enough of them to make up a post.

Be assured that after you’ve done it once, you’ll see how tedious it is — more of a death by a thousand cuts rather than an insurmountable, once-in-a-lifetime-biggest-purchase-of-your-life, if you make it not so.

The how in property buying, as it turned out, is made up of 3 big questions:

- the asset-selection-how, as in the process of finding, filtering, and finalising on The One Property, and then there’s…

- the buying-process-how, as in how do I start and who do I engage?

- the getting-funding-how, as in how do I come up with this most intimidating amount of money in my life so far?

With regard to the first and the second hows, there's been a plethora of content covering the asset-selection-how and the buying-process-how on any real estate media. They’ve came up with frameworks to help get one’s head around the concepts, considerations, and mindset, which is just as well: the more comfortable people become with residential property, the better it drives their business, playing their part to facilitate for those who want to get into property.

The incentives and the outcome aligned.

Though everyone has something to sell, but that doesn’t mean that it’s all shill. That’s the kind of black-and-white thinking that we don’t do here. This asset selection framework in particular, to me, have captured the essence of residential property selection:

Which could be summarised as:

In Affording your First Home, the focus is to share my observations on how banks and lenders think when it comes to granting a mortgage. Keep in mind that though I’ve worked on banking applications before, including building a literal mortgage software product, this is not a financial advice, as usual.

If you’re here, you weren’t asking about “should I buy a property”, but that you’ve already decided that “yes, I would like to buy a property, how do I do it?”

Before You Buy: Assembling the Team

Buying a property, as a first home buyer, is hard. Not because it’s rocket science, but that before one even starts to look for a property, there’s about 1000 paper cuts from the checklists to tick and people to organise, when you don’t know who to talk to and everyone seems to be in a rush all the time.

Agents are always on the phone, brokers asking you about things you haven’t even thought about before, such as how is one supposed to know whether to go for an Investment Property first or a Principal Place Of Residence first? I thought you could advise me on that!

If it all seems daunting, be assured that the first time is the hardest. So how does one start?

Pick a professional; any professional.

Personally, I'd start with a mortgage broker, because without the bank money, I'd still be too poor to afford any property with my cash alone.

Starting with a financial adviser is also an excellent idea, as they could help you figure out your finances, and work with you on a plan to afford a property. When you go directly to mortgage brokers, you essentially represent yourself as your investment manager, and the assumption is that you are fully aware of what part does this property play in your overall lifestyle goals.

Whoever you go first with, ask them for referrals to fill up the roster for the rest of the team, as any professional never works alone in any multi-step endeavours.

Pre-purchase:

- lender: get you the bank money (mortgage).

- banker: you get access to one lender's offerings

- broker: you get access to more selection of lenders in their network. Not all lenders available, but they can compare more products — across banks and other lenders — rather than single lender bankers.

- financial adviser: optional. Hiring a qualified financial planner helps you learn about managing your money quicker, including making a roadmap on how you can afford a property.

Ask grants and overall strategy questions, and you can consult them on your money management things going forward, including forming your investment portfolio.

If you want to learn how to create your own wealth portfolio, it is possible to study the techniques and mental conditioning yourself, but have a realistic expectations of yourself that if you do this in your spare time, expect that it’ll take several years to learn the basics, depending where your start at, and a lifetime to master. - buyer’s agent: optional, but does all the coordination for you. They work with you on your brief, recommends properties that match that brief, and you say yes/no to them. What can take ~1—6 months can be compressed into ~1 month from start to finish, if you're willing to pay for it.

- tax agent: optional. It's more important if you're buying an Investment Property or a flip. Does this deal make sense after tax? Ask tax questions, like Capital Gains Tax (CGT) and deductibility of certain expenses.

Buying:

- conveyancer/solicitor: to review the property purchase contract and work with the banker/broker to settle the amount. Property contracts could have funny things, such as easements, covenants, and other things that allow other people to legally do their things on your property. If buying an apartment, a solicitor can search the body corporate minutes and flag potential troubles.

- building & pest inspection: what is it that you’re buying? It doesn’t guarantee tip-top conditions on the property, but it points out potentially critical failures, things like the roof might cave in 2 years’ time, or that the foundation has shifted. In NSW you can buy this off the listing, but in other states you have to do this yourself.

Post-purchase:

- property manager (if buying an Investment Property): takes care of collections, arrears, rental reviews and arranging trades for maintenance requests.

- trades (if self managing or Principal Place Of Residence): to fix the things you’re not legally allowed to fix, such as installing electrical outlets, or if you have an allergy to changing a lightbulb.

When You Buy: Qualifying for the Mortgage

As a French friend put it, “mortgage literally meant mort-gage, or dead-pledge. You pay the debt until you die.”, she said, during her housewarming party.

Instead of saving $20,000/year for the next 50 years to buy a $1,000,000 property 50 years later, you can now buy a $1,000,000 property with $200,000 — or 10 years, and pay the rest within 30 years.

If the property is priced at $1,000,000, the only thing that the seller cares about is that $1,000,000 is paid out, not how or where the buyer came up with $1,000,000.

With the ~20% of the money to buy coming from savings, there’s only ever 2 levers: how much you can earn, and how little you can spend.

If ~80% of the money to buy the property comes from a mortgage, it follows suit, then, that focusing your effort on the 80% is the best use of your energy. If you want to understand how banks think, you can read the full deep dive in Contracts Explained: The Anatomy of a Home Loan.

If you just want to know how to get a mortgage, the first thing you have to get clear on is how does one define affordability, and what are you willing to trade off?

Affordable Upfront

Affordable upfront means that you have enough to cover for the costs of buying a property and to pay for the equity component of the property price, which according to the bank’s minimum Loan-to-Value-Ratio requirement of 80%—95% LVR, translates into affording to pay for 5%—20% of the purchase price after all buying costs.

When you go speak to a lender/broker, if you give them the price range of the properties you’re looking at, they could give you an estimate of the total down payment that you should aim for to afford the property you’re after.

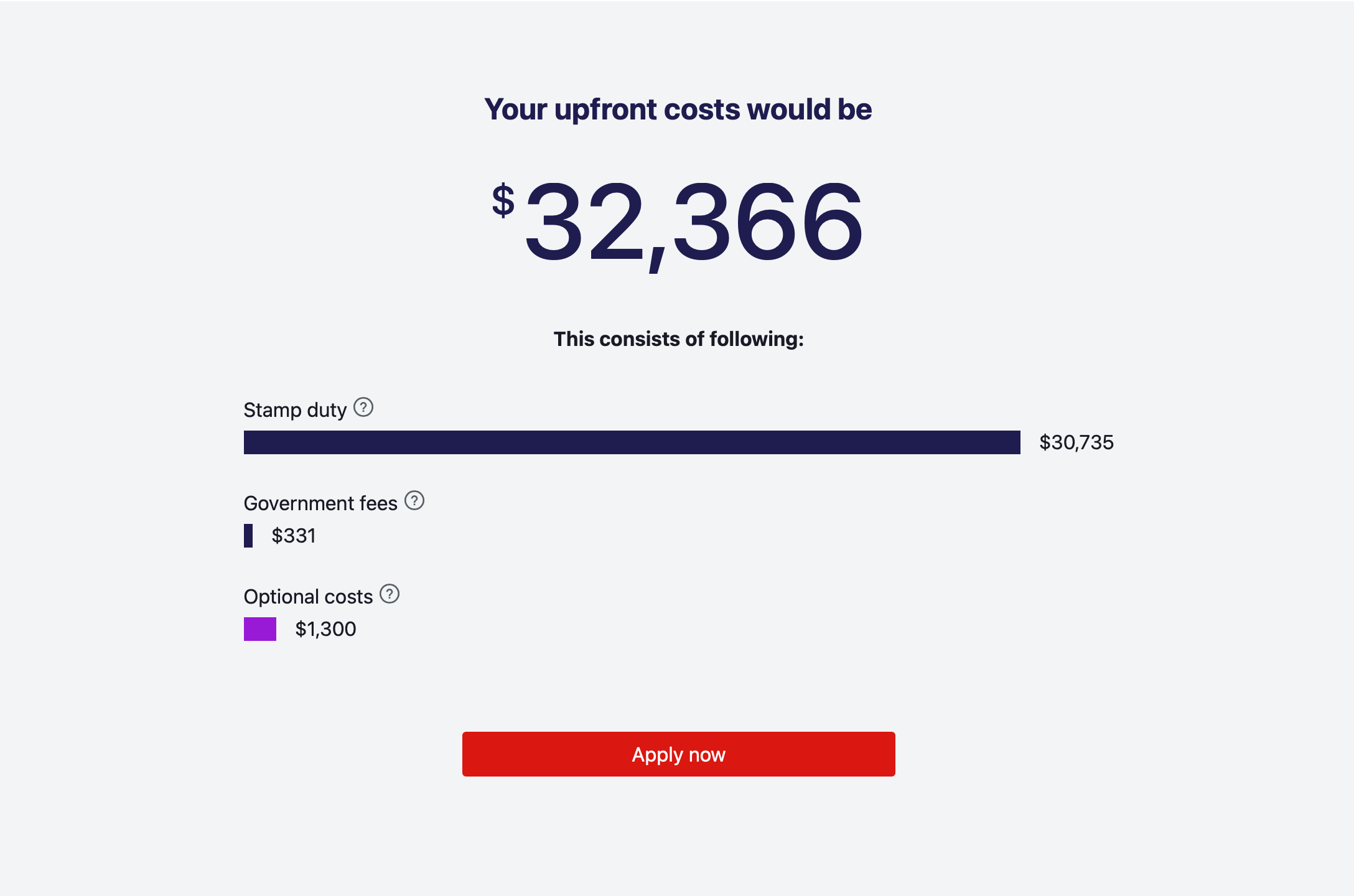

This is not as easy as calculating 20% of a purchase price, because the fees involved are a mix of fixed costs (legal fees etc.) and sliding scale costs (for example Stamp Duty), so the best way is to either ask the lender for the $ figure, or use an online purchase costs calculator and work it backwards to find the price v savings that’s affordable.

To make a mortgage affordable upfront, there are only 2 ways:

- have more money:

- save more faster, or

- buy with more people

- lower the price:

- get more discounts through government grants,

- or buy something cheaper.

Lenders’ Mortgage Insurance falls under the “have more money” part, for reasons you can read up on in Contracts Explained: The Anatomy of a Home Loan. This allows you to put in less equity upfront, at the cost of higher repayment over the life of the loan, making it less affordable ongoing.

Affordable Ongoing

If you want something that you can repay comfortably, it means that you prioritise ongoing affordability.

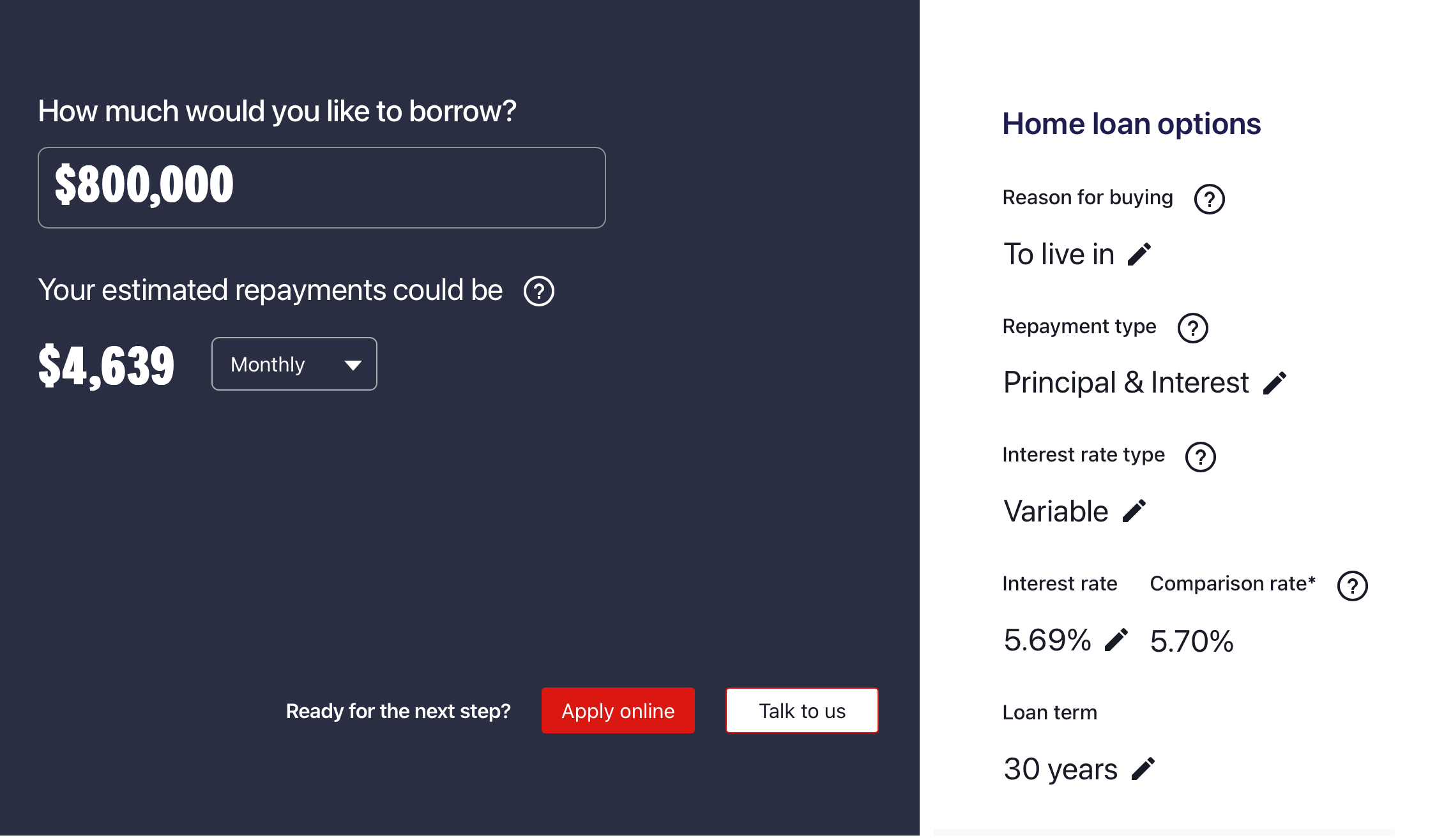

This, too, has a convenient online calculator these days, where you can put in the rough amount that’s going to be borrowed to see how much you potentially will be up for each month.

Ongoing affordability is tied to how much you can borrow, and how much are you willing to borrow. How much you can borrow is based on the assessment of your free cash flow, meaning what you take home after all living costs and other loans, which is called serviceability.

There are also only 2 levers when it comes to making a loan more affordable ongoing:

- have more

moneyequity: repay more and repay often - lower the price: buy cheaper by borrowing less

Implicitly, when someone prioritises upfront affordability, what they prioritise is to get into a property as soon as possible. The price they commit to paying is to pay more each month, having weighed that the lifestyle improvement that the property will bring is worth the extra squeeze in cash flow each month.

Conversely, when someone chooses to go after lower repayments, they value the comfort of having enough money each month rather than what the property will bring into their life.

Upfront affordability is the battle of the people who start out without capital, and ongoing affordability is the battle of everyone who lives in fear of debt.

You have to choose at least 1, and both ways are difficult. Choose wisely.

Between LVR and Serviceability, the final figure a bank will lend will be the lowest one out of the two.

After You Buy: How to Keep Your Sanity and Your Home

The duality of the property journey is such that in the pre-homeownership stage, there is never a shortage of complaints about how buying a home is too expensive, yet post-homeownership, the same crowd, now exposed to the realities the responsibilities that come with the privilege of a property price growth, is never scant of complaints about maintenance and renovation costs.

After spending $5,000 on asbestos management and who knows how many thousands more on the big red hammer, I hear you, and I can confirm that spending hundreds on Aldi’s Ferrex range is a good value for saving thousands more on trades, if you're willing to work on your house for $0.

Risk, in residential property, mostly lives in the cash flow portion. Banks don’t seize and sell your house the moment the price drops to 50% off its starting price, despite the fact that to the bank, your loan is now a risky loan that’s overleveraged by 180% LVR. It is simply un-Australian to do so.

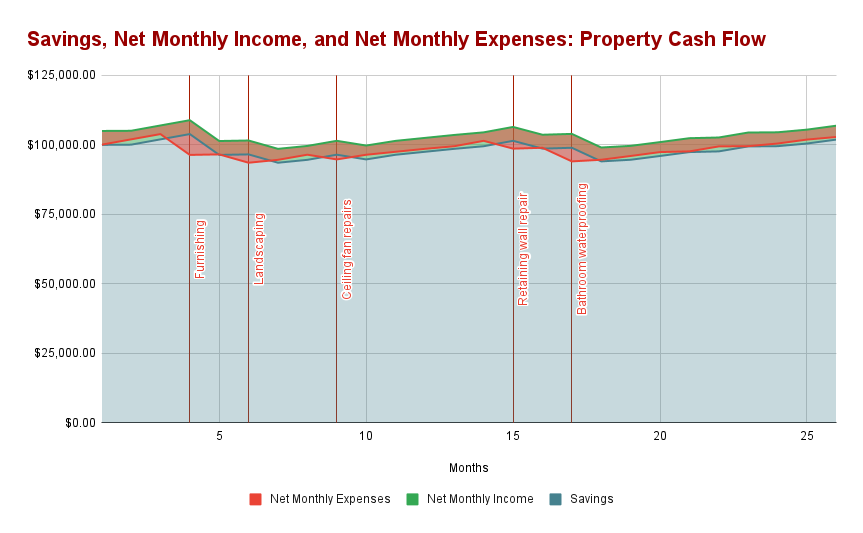

The point of purchase is where real estate media stops. Since everyone has been paid, it's all in your capable hands now, that there is always something to fix, and at times it comes in parcels of $500—$15,000.

Plan for the Unexpecteds

On your personal finances, if you have big ticket items that can’t be covered by your monthly cash savings, you can plan ahead and save to afford it. Property is the same. But unlike people, property doesn't qualify for Medicare benefits.

Remember that with homeownership comes the responsibility for funding various maintenance yourself. What used to be covered by rent, will now come directly at you in $500—$15,000 parcels.

Buying an apartment doesn’t exempt you from building repairs. Instead, you get to play democracy, and have to convince everyone else that yes, this fix is important, please fill up the sinking fund to save us the bigger cost down the line.

Having another 6-months savings buffer just for the property is prudent. This affords the small-medium urgent repairs that insurance doesn’t cover, usually in the range of $500 — $15,000. Coincidentally (or is it?), this matches up with about ~3—6 month living costs, as before.

That way, as you increase your buffer to match the cost of living increases from inflation, you don’t neglect to increase it to cover for the trades’ inflation increases, too.

Always have a buffer for the unexpected repairs. Cash buffers are not to be thought of as “wasted opportunity”, but rather, “sugar injections to finish the marathon”.

A quick aside: to afford expenses in the $X0,000 – $X00,000s, do as banks do, and get an insurance over what you can't afford to pay for yet.

Building insurance covers the cost to rebuild parts of your home, or even the entire home, under a limited circumstances. Contents insurance: self explanatory, but coverage varies so check the fine print.

Banks and insurances, with their access to a wealth of information regarding whether a property is worth insuring or not, are good sources to cross-check if you're about to buy a lemon or an asset. If it's uninsurable, don't even touch it, as even with salvageable cases you'd need a substantial capital to turn it around.

It's not as good as having $X00,000 ready to go, of course, but it covers some of the major ones until you can afford to cover it with your unconditional money.

Test Your Cash Flow

Before you get a loan, banks were already required to build some safety margin to lower how much you can borrow at that time of granting the mortgage so that you don’t overstretch your borrowing. You can borrow less as the result, but you can borrow safer.

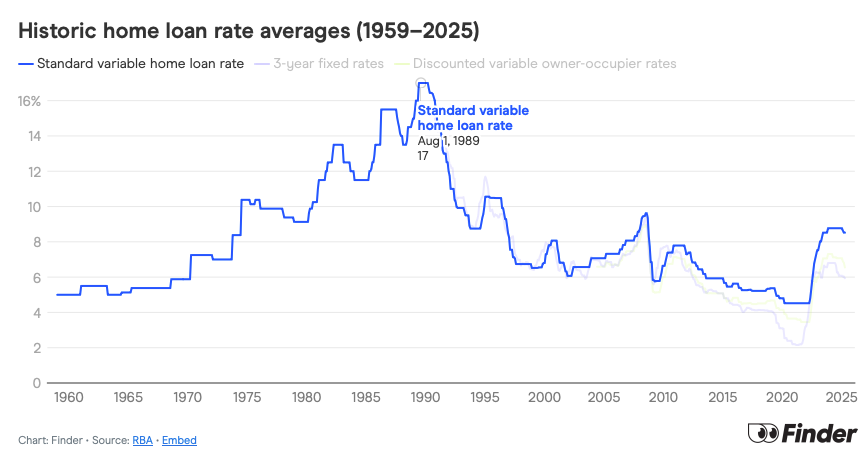

What banks can’t guarantee is that there will be no interest rate raises during the life of your loan, should the wider economic condition calls for it. This is the part that you should model yourself. Historically, 17% interest had happened before, and there's no guarantee that it won’t happen again:

Curiously enough, I couldn’t find any sites that can quickly generate an interest-to-dollar repayment conversion table, which is more useful rather than changing the interest rate one by one. Here's a very rough one for you to give an idea of how much your repayments can jump to:

Mortgage Repayment Table Generator

| Interest Rate (%) | Monthly P&I Repayment ($) | Monthly IO Repayment ($) |

|---|

This was how we were able to afford the recent ~6—7% interest rate comfortably: because we knew that 2—3% interest rate is the exception, not the norm. If anything, 6—7% interest rate is the historical average norm, so plan to afford that for the next 30 years.

When it comes to holding property, let cash flow be your excellence. The personal cash flow is the one thing you have some control over, and the better you are at creating a margin of safety, the higher your quality of life will be. This is life in general, but is especially important the more dependants you have to cover for.

A property is a dependant. You are no longer earning to cover for yourself, but also for a property that requires maintenance and upkeep.

When it comes to capital growth, let time be your friend. What the market thinks your property is worth this quarter is nowhere as important than how it serves you in the context of your life for the next decade, if only for the fact that no one person has control over the entire market direction.

A Timeline of a Decade or More

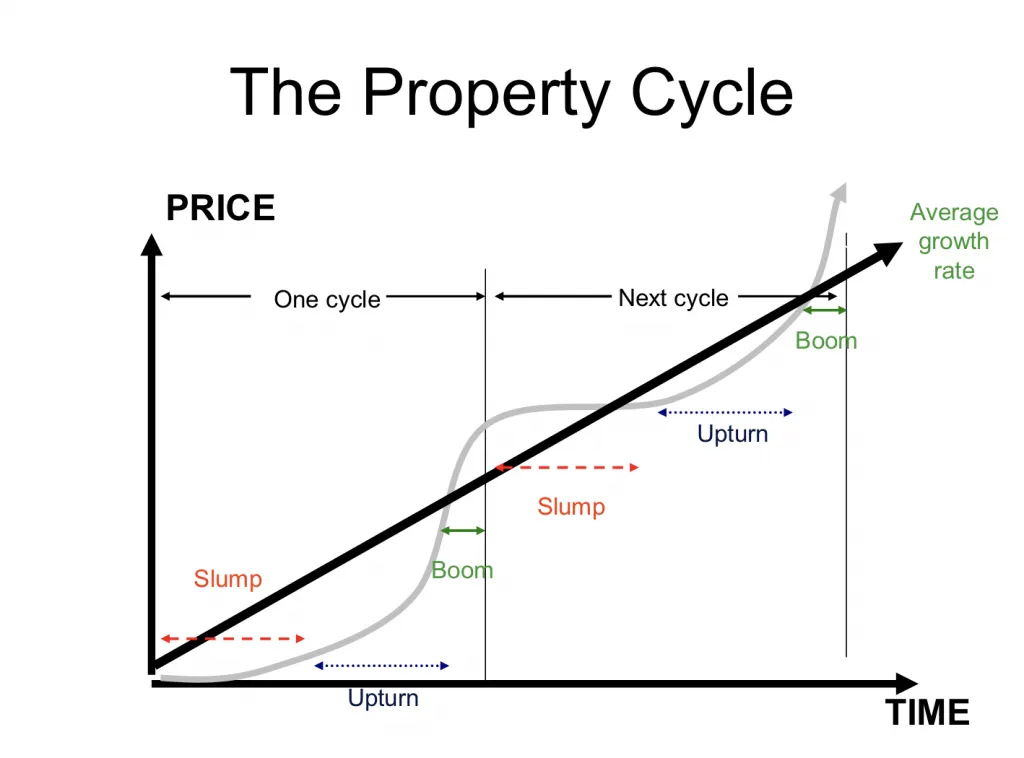

Australian residential property, very roughly, moves in a cycle of a decade, and every region has its own micro-climates. The drivers are different everytime, so are the exact length, such that there’s been lots of star chart reading in the attempt to making it more predictable. And yet, without the ability to predict the future, no one’s been able to do better than sounding confident about it.

While it doesn’t help in timing the precise entry point to buy in order to maximise the total returns, what this means is that when you buy a property without any other competitive edge, expect to buy it for the next 10 years.

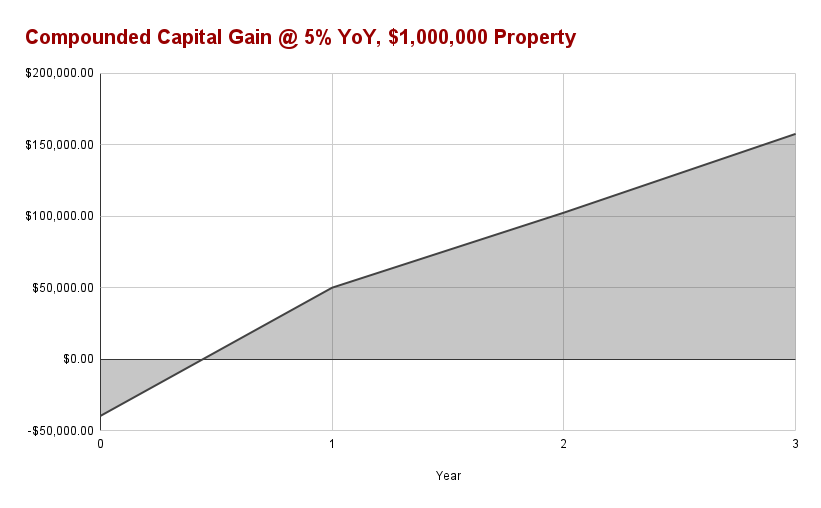

The fully-intended consequence of stamp duty to deter property speculations is that buying and selling property is expensive, meaning that you start with a -$39,735 on a $1,000,000 property from day 1.

If you’re planning for selling within 1—5 years, you should have a competitive edge that’s better than “waiting for the market movement”, because a 5% gains to cover this shortfall is, for the most part, blind luck of the market movement.

This is where people fuss about finding the “hidden upside”, such as qualifying for a grant to be exempt from Stamp Duty, having a free land component to chop and sell (subdivision), or having the trades skills and/or partner to save on the 20% builder’s margin. This is why most flippers are a builder’s [adjacent-someones]: partner, child, cousin or close mates. Their access to wholesale labour and materials subsidised the deal.

In lieu of that, let time be your friend. Give it (and yourself) time to learn and grow.

If you find that you’d like to make residential property flipping your thing, make some builder mates or learn some trades. With the privilege of an insider, your subsequent returns will be better, as you find more ways to sweeten the deal.

Looking into 10 years in the future is hard. The best thing you can do is prepare for the worst, and hope for the best.

Hedge Against the Most Regret, Maximise for the Most Joy

What would've been the thing we regret the most?

Because there's the two of us, we had to approximate two priorities into one consensus.

The most regret, for my partner, was to be stuck in a perpetual state of renting, as he had been for the past nearing-two decades. He had come to a time in his life where having to move every few years became laborious, and the yearly inspections, intrusive. It was, in his proximate words, as if he had no sense of progress; a perpetual renter.

For myself, the most regret would’ve been in the form of us to overstretching ourselves, to the point that both of us have to keep working for the entire 30 years just to afford our family home. I would come to resent it, if not each other, because at that time residential property had become “a solved problem”, having bought on my own few years before we got into a relationship.

Years ago, when I went for an investment property as my first ever home, my most-regret was to be stuck working forever. It was a time where I was working in a place run by apathy and quiet deference to incompetence, so I asked, “how do I never have to work anymore?”

Property is the way out, or so I heard. Why not give it a go? So I did.

With nothing I was able to afford on my own where I lived, that comes with the returns that I was after, I accepted that I'd have to be able to pay more upfront – foregoing stamp duty reliefs and other grants – to buy an interstate property, because having options in the form of the most gains for the least drain on my cash flow, was more valuable than living the Australian dream, if said dream must be paid by enduring that kind of life for the next 30 years.

As I moved on to work at a better place, I came to discover that what I wanted was the privilege to choose work – that is, to work with good people, who both care about the work and the people they work with, on the kind of work that's enriching mentally, physically, and monetarily – rather than to never work anymore.

What did the most joy look like for us then?

For him, this would've been his first home. Joy, for him, was in the form of stability, and yes, that accomplishment of having afforded the Australian dream. A place that’s ready to live in, a bigger space to start a family in the future, and it was a pure coincidence that it came in the shape of an almost quarter-acre block... with a hills hoist at the back.

As for me, getting a home of our own was an opportunity to try my hands out on home improvements, both from a life enjoyment perspective, and to build some sweat equity. That's why I didn't want a "perfectly renovated place", because I wasn't willing to pay the premium on a flipper's renovation that's made for a mass appeal. Yes, let it be known that I am neither short in wants, nor the impetus to go after them.

Of course, it didn't turn out quite the way we envisioned it, as from the returns and enjoyment perspective we could've gotten more for our dollars. We are constantly reminded of this when see another lot being knocked down, subdivided, and be rebuilt for a brand-new 5/3/2 that he stares longingly at every time we go for an evening walk around the block.

These were all the things that we didn't know that we didn't know about before buying. That our mistake was in that we dreamed too small, even though it seemed to be big enough at that time.

According to our original goalposts, however, this property had afforded us what we had hoped from it: a space to settle down at, with many projects to grow into, and a room with a view from which to write in that afforded me the space to dream bigger for our next decade.

Lastly… Most mistakes are reversible

So don’t kill yourself thinking about what could/couldn’t be.

Paid P&I, but are now realising that you’d like to have more cash on hand? Refinance to release the equity, and switch to IO if you want even more cash on hand.

Rentvested in a different city, only to find out that that particular Sydney apartment would’ve brought in nett $2,000 monthly after all costs? Sell up and chase the cashflow, now that you know that you value positive cash flow more than total returns.

Bought a PPOR, but barely keeping your head above the water? You have a choice to reorganise your other spend to create more cash flow, or sell before the bank repossess it and sell it for you, and after that you’d have some $XY,000 freed up pick yourself back up and try again.

Bought an IP, but losing sleep from the maintenance bleed? Sell and rethink about what investment vehicle suits you more, or if you should stick to maximising your salary for the wealth target you’re after. Property is just one form of asset, which in Australia is one that’s geared towards high leverage, cash flow draining type.

Bought for cash flow, but girlbossed too hard and are now paying too much tax? Sell up, restructure, etc. The stamp duty would suck. So is paying $50,000/year for a university degree that you don’t use. Consider that the cost of having lived, and rebalance.

In any way it goes, you’ll come out richer from having lived this experience.