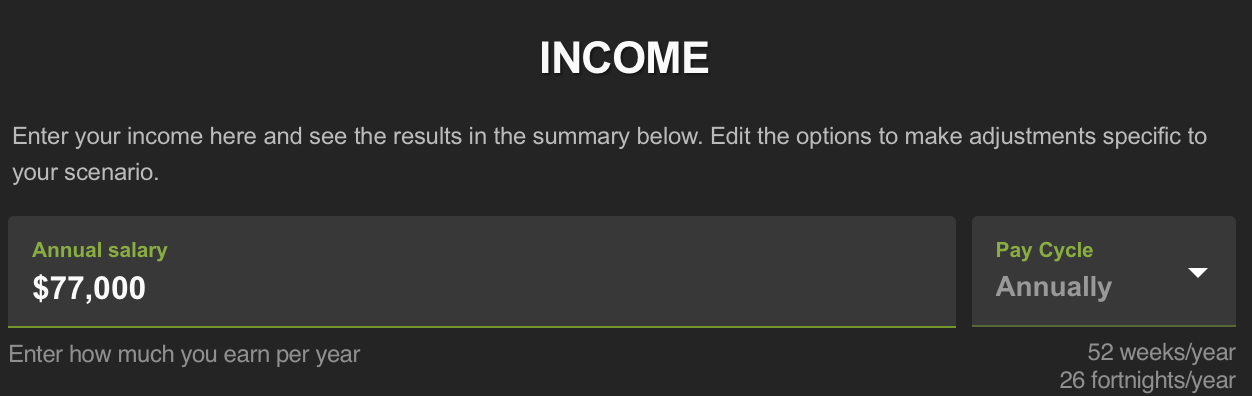

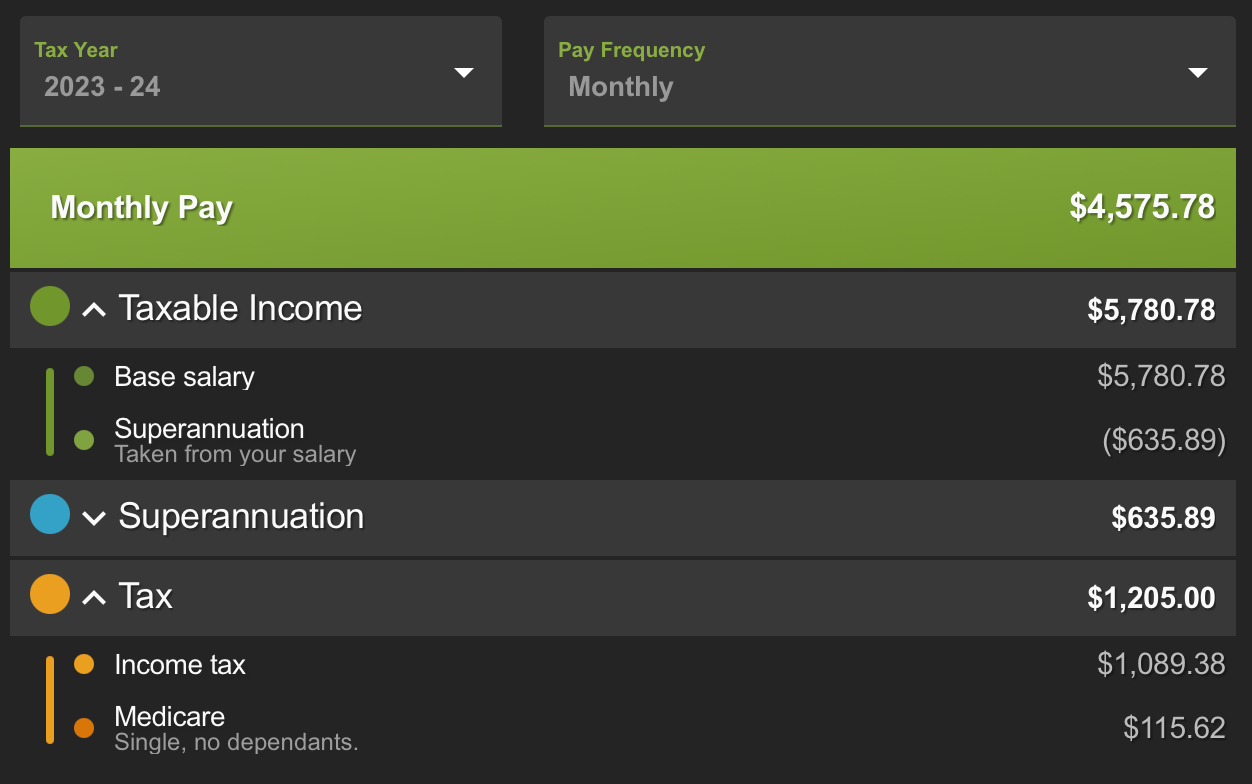

If I were to draw a direct parallel with Woolf’s £500/year of passive income, in a literal measure it’d be worth £39,364.90 today, or roughly $77,000 AUD.

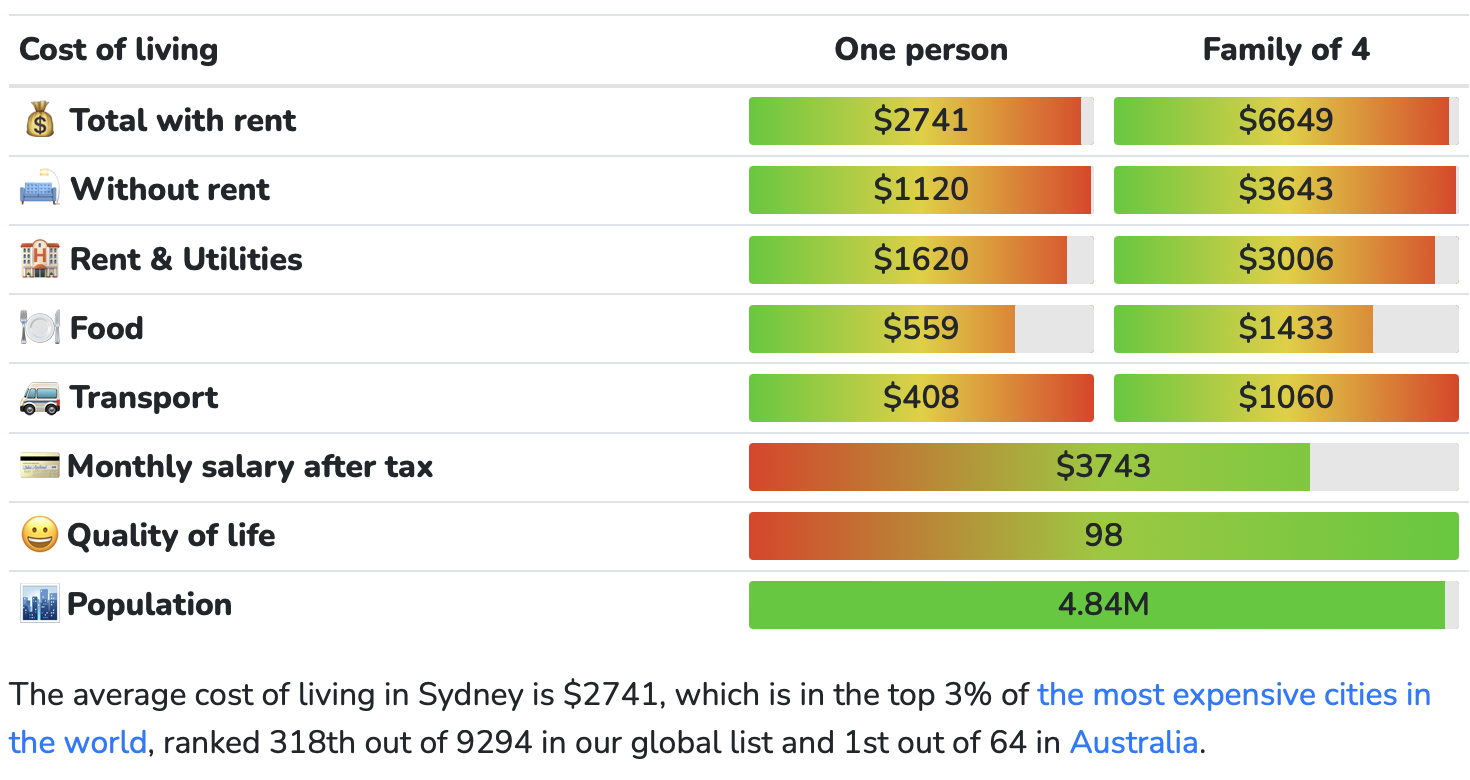

To a single person living in London, on the average cost of living of £34,704, it’s a liveable income.

To a family of four, still in London, living on £58,200, it’s not a liveable income.

If I were to take it at face value and apply it to a single person in Sydney, where I’m based at, $77,000 (gross) income is still a very liveable income, in the sense you can afford to live somewhere and not go hungry. Maybe take an out-of-town holiday or two, even.

For a family of 4 in Sydney, however, it is similarly unaffordable as it is in London.

To earn $77,000 in passive income, mathematically one would “only” need to get to around $2M net asset earning 4% p.a. If you’re in tech or middle-management and above, you can do this by saving $50,000 every year over the next 40 years.

Problem is, how many people can save $50,000/year?

I did it by having no dependants, below-average rent with bills included, no vacations, no subscriptions besides rent, phone and transport, and sticking to free hobbies only.

Now how many people would stay single and rent-share for the rest of their lives, on purpose, just so they can live off passive income?

A grand total of 1, out of all people I’ve met.

Money, on its own, is worthless. It is only valuable in relation to what it can afford of the beholder, be it something that can directly be bought, or in terms of affording second-degree privileges.

A Woman, if She is to Write, Must Have…

In the early days, I thought of my life as one of the forgettable ones. A tolerable existence.

Rich enough for afterschool lessons, but too poor for ballet and piano lessons, I was the good daughter that was could always be better. Then came the penultimate year of my bachelor’s degree.

Having taken the degree as a matter of compliance, I didn’t give much thought into what I would do after graduation. I had gone through the courses the same way I had always been: through the motions.

But that space and time away of my own, where my boundaries weren’t constantly trampled on, was all that mattered. I still didn’t know what I wanted to do or what to be; I only knew what I didn’t want: going back into the box. In the absence of a strong pull, a strong push was enough.

That small taste of freedom had me thinking for myself for the first time.

The first price to be paid was to earn enough money to survive on my own.

Money to Survive

My first job as an adult paid $10/hour, cash on hand.

As you can imagine, in a city where living costed a minimum of $2,000/month, it didn’t take me far.

Having squandered my time at the university to make any promising industry connections, I graduated a subpar candidate. Without connections, you see, why would any sensible business hire an average foreign graduate who needs a visa sponsorship, accruing extra costs from the get-go, when there’s so many citizens and permanent resident hopefuls applying?

Shy, awkward, and bad at talking to strangers, I wasn’t even able to get any casual waitressing job, until a friend referred me into a local corner chicken shop. That was my entry into the Australian job market: cleaning grills, emptying up deep fryers, mopping floors and packing BBQ chickens for $10/hour — cash only.

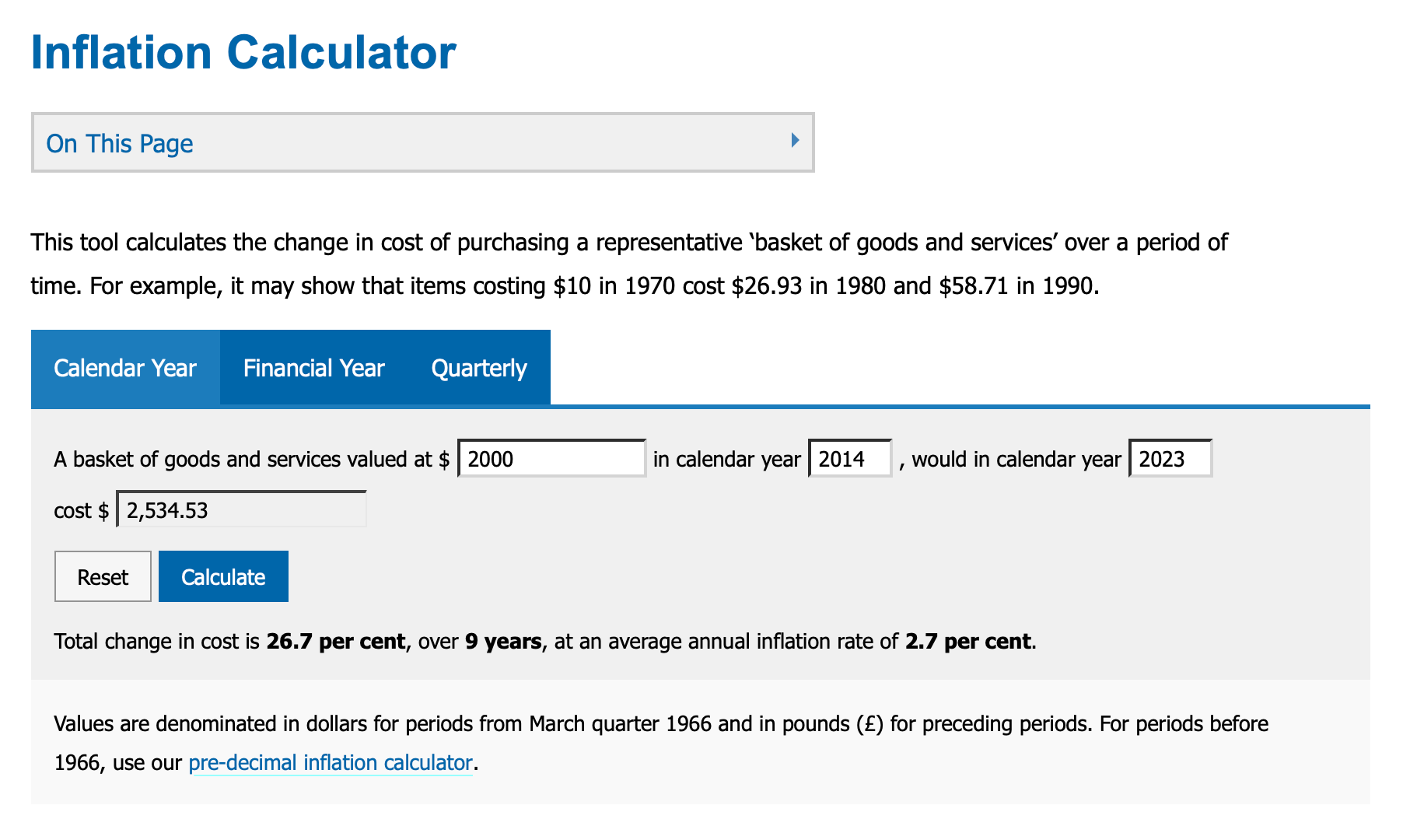

If you’re based in Sydney, you would've noticed that $2,000 is on the low side, even in 2014.

The secret?

Cutting one's corners.

In a polite company, we use nice-sounding aliases such as minimalism or frugality; in the end, they are all about cutting things down... to a point. There's only so much that can be cut until you start compromising your integrity, after all.

This was what a $2,000/month life looked like back in 2014.

A room, at that time, was a sharehouse found off Gumtree. Priced at $830/month bills included, without rental contracts, bonds, or access to the kitchen (but thankfully a fridge), it was the least dodgy place I could afford that wasn’t in a nudist sharehouse or a cupboard.

Sustenance came in the form of end-of-the-day discounted takeaways, padded with frozen vegetables to bring it further down to under $5 per serving.

Hobbies were long walks, not for my Tinder profile, but because it was free and I had — still have, thankfully — working legs.

That I was in my early 20s and had no dependants was a privilege of youth, which granted me the energy to work through midnights and weekends without repercussions, so I could lean out and earn more at the same time.

These were the privileges that I did have and used, in order to offset the privileges of rent exemption, Jobseeker allowance, and Medicare that I didn't have.

Luck was that barring the one incidence of a police raid, the rest of the years living there had been pretty uneventful, save for the noisy housemates. Luck, too, was that I didn’t have to pay with anything else besides the $830/month.

It was pure luck, that in the time that I didn’t buy any insurances to save $100/month, I didn’t get into any accidents.

Most things were circumstantial. They were outside my control. I could risk it all, because I had nothing to lose.

But the skill to make the most of what I’ve got? Priceless. That was the main and the most important skill that I took with me in accumulating $1M during the first decade.

There is no saint or sinner in this story.

You see, in the beginning, even after all that corner-cutting, at times my income still couldn’t meet the $2,000/month minimum required to survive. Especially in the beginning, when I had to do a lot of free work in order to get an in.

If the minimum cost of living can't be covered on your income alone, it has to come from somewhere else. Yes, after all that talk about surviving on my own, I wasn’t able to make it, in the beginning.

I had to take what I’ll call, “the wrong money”.

The wrong money doesn’t always come with bad intentions, but it always comes with restrictions.

The wrong money requires you to act a certain way, do things you don’t want to, and use it only on certain things in order to have access to it. Wrong money controls you. Somebody always has to pay for it, whether it's now or in the future, by yourself or someone who's willing to stand in for you. But the wrong money was better than no money.

People take the wrong money all the time. Money, afterall, dignifies what is frivolous if unpaid for, which is why it’s alright to take an Angel Investor’s money to start a business, no matter how unviable the business model is, or to stay in a job you hate, but not for anything else that does not money-make.

Don’t believe me? Well, what is the general consensus on subsidies?

People don’t look kindly on people who take subsidies, whether they’re from private hands or public pockets. But companies don’t quite get the same judgement, even though both essentially are attempts to bring something that can’t yet stand on its own into something viable.

By dismissing people for “not paying their own way”, it silences the stories of people who had been controlled by money, even when they’re paying in ways other than money.

Money can’t always buy happiness, but it sure can buy freedom, which is the beginning of all happiness.

That $10/hour — a pittance to anyone else, was the first key to my freedom.

This brings us to my second point: that if one were to survive, one must learn to use all the privileges that one have.

The less privileges you can apply in your current context, the better you have to be in using what little you can. It’s not whether one has or hasn’t got any privileges. Everyone has some, and the amount is not fixed. By all means get mad over the unearned privileges you don’t have. But don’t stop there. Realise, that as long as you’re still breathing, you can always earn more privileges.

Some privileges are more far-reaching than the others, but there’s always something that you specifically can use.

Sometimes it’s about hard work, working with all you’ve got to adapt better to your current context. Other times it’s about finding a new context that suits you better, as the expats with strong passports have found, because some privileges become more potent when applied in a different context.

That self-made way would’ve taken away time for building the way into better paying, stable jobs. Time, that I didn’t have, because my obscure visa was only valid for a year. This was my first inkling of the concept of opportunity costs.

6 months down. Still no fulltime jobs in sight. My parents, rightfully, were getting restless, waiting for my market adoption as I burned through their retirement money. 6 months left to break the circular dependency of needing the right visa to get a job to get the right visa, on top of needing the right experience for the first job.

I swallowed my pride and took the one with the highest ROI and the shortest time to profitability, like a good businesswoman.

Pride is for people who can afford to not use everything they have. If one has many other privileges to make it up in number, one does not need to lean so far on the few in order to get ahead.

This is what it means to give it your all. Ask yourself, can you really afford not using everything you have?

Over the next 2 years, in my attempts to join the ranks of the comfortably employed I’ve taken on 9 roles: as a cleaner-kitchen hand, a volunteer CAD drafter, a glorified data entry clerk, a startup “consultant”, an amateur day trader, a casual eBay seller, an unpaid intern, a freelance app developer, and finally, a fully employed junior software engineer.

4/9 roles paid money. 9/9 paid more than money. You won’t see this in my resume, because most things weren’t relevant. This could be said about success in general — that the processes are hidden, until it finally resulted. It wasn’t straightforward, nor it was picture-perfect; it was a real life that I was finally living.

The rest was a relatively stable stretch of period, during which I did the fulltime grind towards my first $1M.

…and a Room of One’s Own

In the beginning, my “room” was an amalgamation of the private and public space. The room that I rented was solely for sleeping in, because it was impossible to think with the paper-thin walls.

Lacking the space to think, I sought quiet places where I can be without having to spend. You’d think that libraries would be quiet, but not all libraries are created equal, and when libraries won’t do, train carriages would; they tend to get very quiet nearing the end of the line, and at a low, low cost of $7 per ride, for the duration of 4 hours, it was very well worth it.

I ended up spending most of my weekends at work, however. It is, hands down, the best and the most underused space to think. All of 1000m2 to myself, and the odd 1-2 persons who would come into the office on the weekend. The price for access was the other 5 days taking care of other people’s businesses.

It might seem sad to a lot of people, but in the context of my seeking space, it was perfect. Nobody who could afford a room of their own comes to work on the weekends. All the tools was there. I’d even cook breakfast sometimes. I spent hours and weekends learning about how to learn better, about programming, about entrepreneurship, and about more ways to make money other than “work harder”.

The answer to the right visa for the right jobs conundrum was to find the people who will accept the not-perfect candidate for the not-perfect jobs, in order to obtain the privilege of the right visa for the right jobs. This was market penetration 101. That right visa itself was a form of extension to my “room”: an earn-able privilege to be, which granted me stability and better opportunities, amongst many other things.

As my financial situation stabilised, I became able to afford more spaces. Gym memberships, cafes, and dance lessons became my extended “rooms” in which I learned more about myself. Live a little more. Try new things. Get to know what I like and dislike, what I will and will not accept, who I am when I’m not told what to think.

I had some lifestyle inflation, but I continued to live in survival mode until the 4th year when I finally acquired the right status. For better or worse, the second real crisis in my short life also happened around that time, which propelled me to accelerate into leveraged investing 101, otherwise known as the Australians’ second religion: property.

That’s another story for another day. Stick around, and you might just get to read it.

Fast-forward 10 years since then. I’m writing this in a room of my own. It’s a 3.5 bedroom house with about 600m2 of garden; there’s enough room for all 2 of us.

In a labour market that has priced double incomes at 2-3 bedroom apartments, even for above-median household incomes, this is certainly the exception, not the rule.

The best part is that we didn’t have to take the wrong money for it.

Having lived and having afforded a room of my own, I’m finally able to sit down to write.